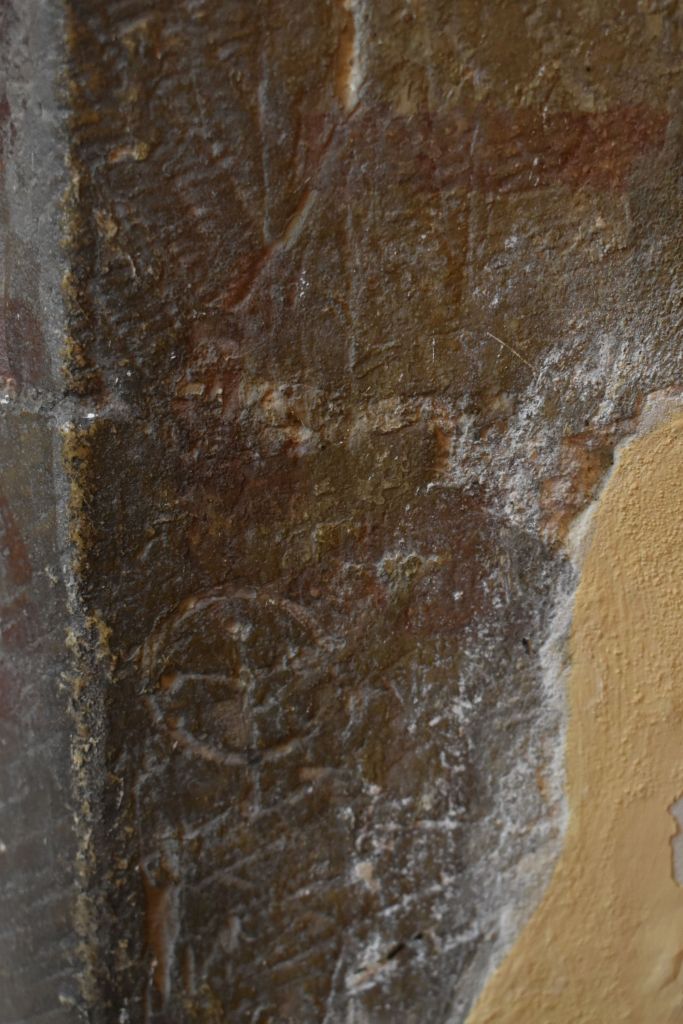

Cross, St Nicholas at Wade, Kent © Carole Tyrrell

Imagine if you will a medieval church. Inside it would be brightly painted and very colourful in contrast to the whitewashed interiors that we are familiar with today. Faded vestiges of these colours can sometimes be seen on monuments or pillars. The church porch might be used for other activities besides keeping out of inclement weather. They were used for ceremonies such as marriages or the ‘churching’ of women and churches were often the hub of community life. But they also had a dark side as they were seen, surprisingly, as places where evil lurked. In fact, it was believed that the Devil and his horde lived within the church on the ‘north’ or sinister side.

The medieval world was often harsh and the forces of evil were supposedly everywhere. A bad harvest, plague or fires were all attributed to them. Witches were also believed to be real. Meanwhile the Church taught that the world was full of evil spirits who were always looking for unwary souls to tempt or possess.

Even churches needed protection despite priests performing blessings and masses and so the local parishioners took action into their own hands and relied on the use of apotropaic symbols. This is a Greek word that comes from ‘apotrepein’ which means ‘to ward off’ i.e. ‘apo’ = away and ‘trepein’ = ‘to turn.’ It was a secret language which its medieval creators firmly believed could protect them from evil. They were a way of their creators taking back control over their world. The marks were often inscribed near vulnerable places such as doorways, windows, fireplaces and even fonts. In other words, wherever an evil presence might try to enter. But they were not confined to churches as they also appeared in other historic and ancient buildings.

Daisy wheel on fragment of a demolished house in Essex, Southend Central museum. © Carole Tyrrell

But by the 18th century, belief in protective marks had declined. However, they were inscribed into buildings and churches up until the 19th century and have been described as ‘folk magic’ or superstition. But in rural areas the tradition continued and was handed down through generations.

I have seen many medieval survivors of the 17th century iconoclasts in Kent churches such as wall paintings at Selling and a Doom painting at Newington but more recently I have been finding the most enigmatic survivors of all, ritual protection marks. You have to know where to look as they are often well hidden. I did wonder if the priest knew what was going on and turned a blind eye. But we will never know. However, this is a huge subject and I can only scratch the surface. I’m just intrigued by them and their variety. In this post I am giving you a selection of what I’ve found so far and possible meanings. I have visited 3 churches so far: St Nicholas, Sturry, St Nicholas at Wade and Hoo St Werberga who all have these marks. As you might imagine crosses feature heavily.

Figure on pillar, St Nicholas, Sturry.© Carole Tyrrell

I first found marks in St Nicholas church, Sturry, near Canterbury in 2023. The churchwarden pointed them out as they’d just had someone in to do a survey of them. There were crosses on pillars near the entrance and on the other side of the church. So, I made a return visit this year and this time found a figure which may be the Virgin Mary as it seems to be wearing a skirt and has a halo.

However, there was a Facebook post dated 27 December 2025 on the Ritual Protection Marks and Ritual Practices page in which they say that this particular mark may be a Golgotha mark which represents the site just outside Jerusalem where Jesus was crucified. I can’t put a link to it but if you visits the page it’s easy to find. This is an interesting page and they know what they’re talking about.

There was a little note on a pillar indicating a M or Marian mark but I couldn’t find it and then I was distracted by a cream tea. I also saw circles which appear to have been appear to have been drawn with a compass as well as dots. The small circles are also referred to as hexafoils and are the most common.

Circle, St Nicholas, Sturry, © Carole Tyrrell

According to their information leaflet on the marks;

‘They can range from simple circles, to six petalled flower designs and highly complex geometric designs which are known as daisywheels.’

They are usually small as at St Nicholas, but they can be up to a metre across. It was originally believed that they were created by the masons who built the churches but there are too many for them to be attributed to one trade. It has been suggested that:

‘they may have been created in order to trap the demons that roamed the world within their complex structure by quite literally pinning them to the walls.’ Information leaflet, St Nicholas, Sturry.

Also at Sturry , there are five ‘dots’ on a pillar which could easily be missed but they have significance:

Dots on pillar, St Nicholas, Sturry. © Carole Tyrrell

‘the dots appear to follow numerical values, being found in generally uneven numbers, and commonly in groups of three, five, seven and nine. Certain uneven numbers had considerable significance in the medieval church, such as the Trinity and the seven sacraments, and numbers were also regarded as powerful within aspects of medieval magic’. Information leaflet, St Nicholas, Sturry

But this is only one interpretation and, as with most ritual protection marks, there can be several and it’s not possible to say definitively which is the correct one.

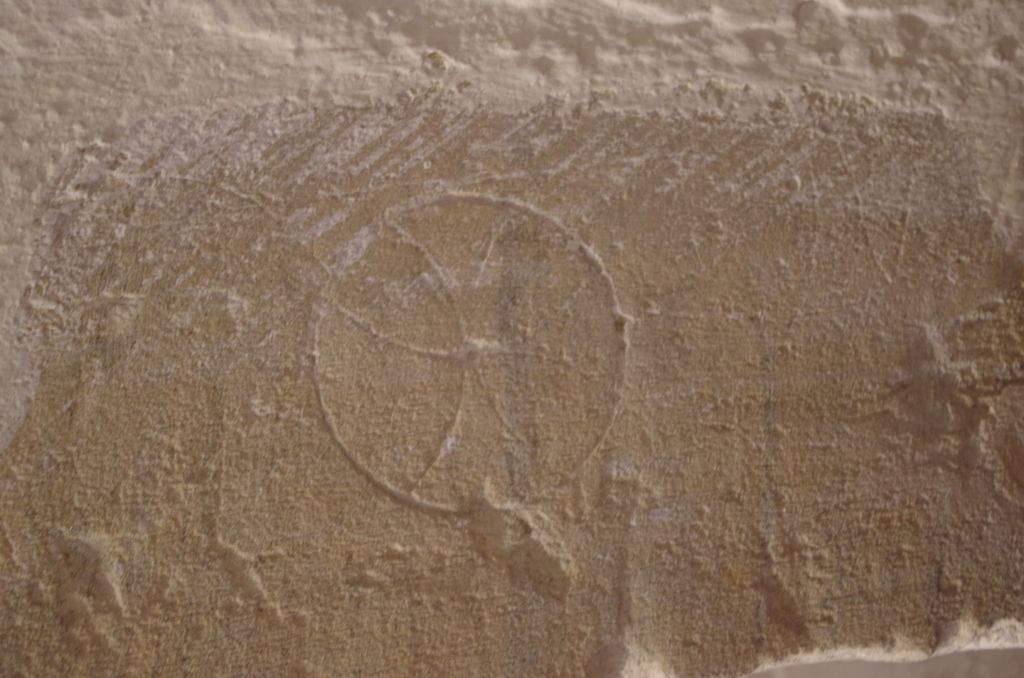

I visited St Nicholas at Wade at Easter 2025 and the church was bustling as it was being decked with flowers for the celebrations. They very proudly showed me their ‘daisy wheel’ on a pillar.

Daisy Wheel, St Nicholas at Wade. © Carole Tyrrell

A daisy wheel is a stylised flower pattern and according to English Heritage ‘

‘they are the most easily recognisable. They have been found in early medieval English buildings from the early medieval period right up to the 19th century. Followers of Wicca see them as sun symbols’

Histories and Castles describe them as:

‘geometric rosettes, often with 6 petals that symbolised eternity and divine protection. The medieval mind believed that evil travelled in straight lines and so could be trapped by circular forms, the looping unbroken line of a hexafoil was thought to confuse evil spirits or trap them in an endless journey.’

I previously visited Hoo St Werberga in September 2024. But this time I was looking specifically for ritual protection marks and found them despite being led astray by another excellent cream tea. This time I found a large ship on a pillar which is possibly a reference to St Werberga’s position on the River Dee and the lantern in its tower to guide shipping. My photo did not come out too well although the body of the ship can be seen. So, I attach a copy of a far better photograph that was displayed on the local history desk with their kind permission.

Ship on pillar, Hoo St Werberga. © Carole Tyrrell

In fact it was one of the local history people who proudly indicated one of the most enigmatic and mysterious marks I’ve seen so far. It was a bullseye on a pillar. It was partly obscured by the organ and other pieces of church furniture and so I might have missed it. He told me that they know nothing about it and it’s certainly an unusual item to find in a church. . However, the circles inside each other may have been another method of trapping demons.

Bullseye, Hoo St Werberga. © Carole Tyrrell

I will undoubtedly find more as I explore other churches in Kent especially as I now know where to look for them. They are the traces of a medieval belief system of protection from the threat of unknown demonic forces from which no one was safe not even the rich and powerful. They were seen as holding protective powers and were a way of empowering their creators.

They are a fascinating glimpse into the world and beliefs of our ancestors.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading:

392 WITCH MARKS v2.indd (the Fortean Times article on witches marks from 2019)

Witch marks: Medieval graffiti for protection

Witches, Carpenters & Masons – what’s in a mark?

What Are Witches’ Marks? | Historic England

APOTROPAIC / RITUAL PROTECTION MARKS – GAUDIUM SUB SOLE . SUNDIALS . MEDIEVAL TO MODERN

Apotropaios – Home (one of the best sites on these marks.)

Magical House Protection – the archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft – Brian Hoggard, Berghahn, 2019

Information leaflet, St Nicholas, Sturry, Kent