This is another older post about a symbol that is not common within churchyards and cemeteries and so I am always thrilled whenever I see an example. This gorgeous example is in below is in the interior of St Nicholas’ church in Chislehurst, Kent. It’s dedicated to a woman and perfectly illustrates the use of the butterfly as a symbol of transformation and resurrection.

As the lockdown edges closer to more restrictions being relaxed, I hope to be out exploring again very soon!

<!– /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:””; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:10.0pt; margin-left:0cm; line-height:115%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; margin-bottom:10.0pt; line-height:115%;} @page WordSection1 {size:595.3pt 841.9pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} –>

©Carole Tyrrell

<!– /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:””; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:10.0pt; margin-left:0cm; line-height:115%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; margin-bottom:10.0pt; line-height:115%;} @page WordSection1 {size:595.3pt 841.9pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} –>

©Carole Tyrrell

<!– /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:””; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:10.0pt; margin-left:0cm; line-height:115%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; margin-bottom:10.0pt; line-height:115%;} @page WordSection1 {size:595.3pt 841.9pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} –>

©Carole Tyrrell

copyright Carole Tyrrell

Cemeteries and graveyards can be happy hunting grounds for butterflies. But not just the bright, dancing summer jewels, borne on the breeze, but also the much rarer kind which perches in them for eternity.

So far I’ve only discovered two of this particular species which were both in London. One was in Brompton and the other was in Kensal Green. But I have also seen others online in American cemeteries.

But I’m surprised that the butterfly symbol isn’t more widely used as it is a deep and powerful motif of resurrection and reincarnation. It has fluttered through many cultures which include Ancient Egypt, Greece and Mexico.

In classical myth, Psyche, which translates as ‘soul’, is represented in the form of a butterfly or as a young woman with butterfly wings. She’s also linked with Eros the Greek God of love. It is also a potent representation of rebirth and in this aspect, the Celts revered it. Some of the Ancient Mexican tribes such as the Aztec and Mayans used carvings of butterflies to decorate their buildings as certain butterfly species were considered to be reincarnations of the souls of dead warriors. The Hopi and Navaho tribes of Native American Indians performed the Butterfly Dance and viewed them as symbols of change and transformation.

The butterfly is an archetypal image of resurrection in Christianity and this meaning is derived from the 3 stages of a butterfly’s life. These are: 1st stage = the caterpillar, 2nd stage = the chrysalis and 3rd and final stage = the butterfly. So the sequence is life, death and resurrection. The emergence of the butterfly from the chrysalis is likened to the soul discarding the flesh. It has been depicted on Ancient Christian tombs and, in Christian art, Christ has been shown holding a butterfly. It is supposed to appear chiefly on childrens memorials but the two that I’ve seen were on adult memorials.

Butterflies also feature in Victorian mourning jewellery and there is a fascinating article on this with some lovely examples at:

http://artofmourning.com/2014/10/25/butterfly-symbols-and-19th-century-jewellery/

In the 20th century, butterflies appeared in the flowing, organic lines of Art Nouveau and often featured in jewellery and silverware.

Face and butterfly on exterior of chapel.

copyright Carole Tyrrell

This example is from the Watts Chapel in Surrey and shows the flowing lines and stylised butterfly. They also appear in vanitas paintings, the name given to a particular category of symbolic works of art and especially those associated with the still life paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries in Flanders and the Netherlands. In these the viewer was asked to look at various symbols within the painting such as skulls, rotting fruit etc and ponder on the worthlessness of all earthly goods and pursuits as well as admiring the artist’s skill in depicting these. Butterflies in this context can be seen as fleeting pleasure as they have a short life of just two weeks.

Butterfly traditions

There are many superstitions and beliefs associated with butterflies. They are often regarded as omens, good and bad, or as an advance messenger indicating that a visitor or loved one is about to arrive. In Japan, they are traditionally associated with geishas due to their associations with beauty and delicate femininity.

![Butterfly & Chinese wisteria by Xu Xi Early Sing Dynasty c970. By Xü Xi (Scanned from an old Chinese book) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://shadowsflyaway.blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/butterfly-chinesewiki.jpg)

By Xü Xi (Scanned from an old Chinese book) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Chinese see them as good luck and a symbol of immortality. Sailors thought that if they saw one before going on ship it meant that they would die at sea . In Devon it was traditional to kill the first butterfly that you saw or have a year of bad luck as a result. In Europe the butterfly was seen as the spirit of the dead and, in the Gnostic tradition, the angel of death is often shown crushing a butterfly underfoot. In some areas in England, it’s thought that butterflies contain the souls of children who have come back to life. A butterfly’s colours can also be significant. A black one can indicate death and a white one signifies the souls or the departed. It’s also a spiritual symbol of growth in that sometimes the past has to be discarded in order to move forward as the butterfly sheds its chrysalis to emerges complete. So it can indicate a turning point or transition in life. There are also shamanistic associations with the butterfly’s shapeshifting and it has also been claimed as a spiritual animal or totem.

Brompton Cemetery, tomb unknown

This example with its wings outstretched is from Brompton Cemetery in London. Alas, the epitaph appears to have vanished over time and the surrounding vegetation was so luxuriant that I will have to return in the winter to investigate further. Note the wreath of ivy that surrounds it. Ivy is an evergreen and is a token of eternal life and memories. The wreath’s ribbons are also nicely carved.

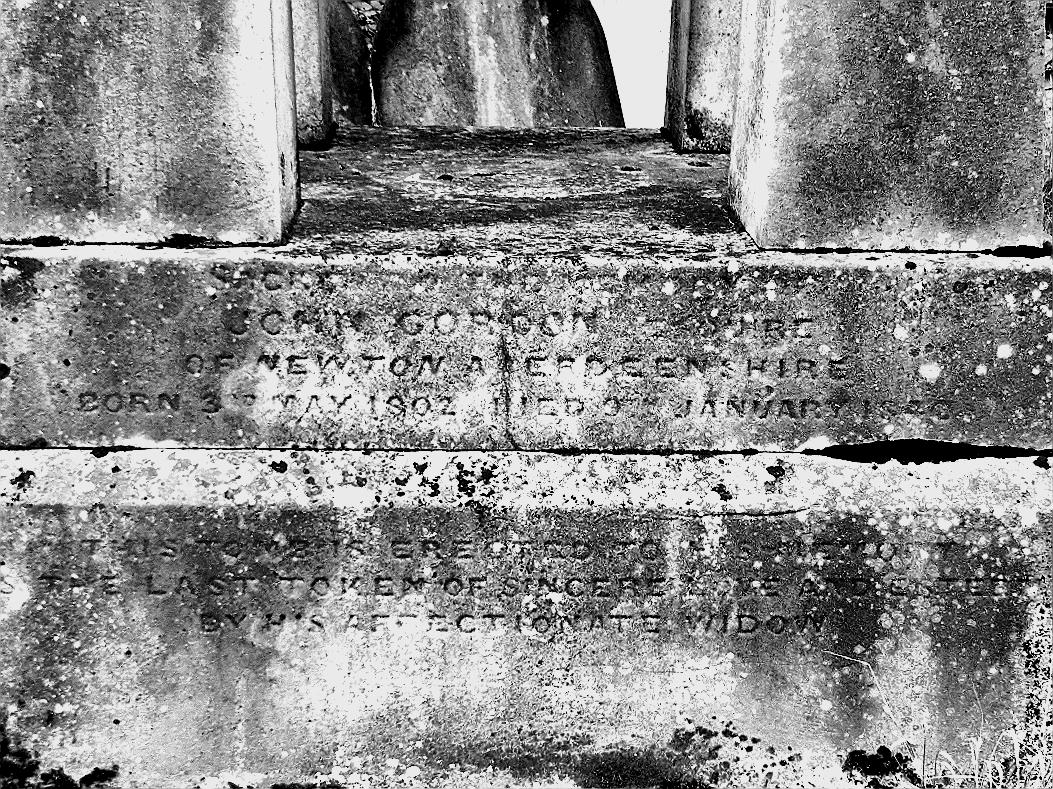

The Gordon monument, Kensal Green

The second one is perched on the tomb of John Gordon Esquire, a Scotsman from Aberdeenshire who died young at only 37. As the epitaph states ‘it was erected to his memory as the last token of sincere love and affection by his affectionate widow’. Gordon came from an extended family of Scottish landowners who had estates in Scotland and plantations in Tobago amongst other interests. The monument is Grade II listed and is made of Portland stone with a York stone base and canopy supported by the pillars. There was an urn on the pedestal between the four tapering stone pillars but this was stolen in 1997.

The butterfly also has an ouroboros encircling it so, not only a symbol or resurrection, but also of eternity with the tail devouring snake. It is a little hard to see but it is there.

copyright Carole Tyrrell

The pharaonic heads at each corner are Egyptian elements within an ostensibly classically inspired monument. Acroteria, or acroterion as is its singular definition, are an architectural ornament. The ones on this monument are known as acroteria angularia. The ‘angularia’ means at the corners.

The entire monument is based on an illustration of the monument of the Murainville family in Pugin’s Views of Paris of 1822 and also on Moliere’s memorial which are both at Pere Lachaise in Paris.

The Gordon memorial incorporates elements of the Egyptian style and symbolism that influenced 19th century funerary monuments after the first Egyptian explorations. Kensal Green contains many significant examples and there are others to be found in Brompton, Highgate and Abney Park. The Victorians regarded the Egyptians highly as it was also a cult of the dead.

So when you next see a butterfly fluttering on the breeze or even perched on a memorial for eternity remember its importance within the tradition of symbols, religions and cultures. Who knows it might be one of your ancestors…..

© Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References:

http://www.gardenswithwings.com/butterfly-stories/butterfly-symbolism.html

http://www.whats-your-sign.com/butterfly-animal-symbolism.html

http://www.spiritanimal.info/butterfly-spirit-animal/

http://www.pure-spirit.com/more-animal-symbolism/611-butterfly-symbolism

http://www.bbc.co.uk/london/content/articles/2005/05/10/victorian_memorial_symbols_feature.shtml

http://www.thecemeteryclub.com/symbols.html

https://stoneletters.com/blog/gravestone-symbols

https://www.reference.com/world-view/butterfly-symbolize-cf9c772f26c7fa5

https://www.reference.com/world-view/butterflies-symbolize-19a1e06c9c98351c?qo=cdpArticles

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Butterfly

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanitas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acroterion

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1191024

Clare Gibson, How to Read Symbols, Herbert Press 2009

Douglas Keister, Stories in Stone, A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography, Gibbs Smith, 2004

J C Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, Thames & Hudson 1978.