Close up of head, ‘monumental’ brass, St John the Evangelist, Margate. ©Carole Tyrrell

It was dark in the chancel as I explored St John’s and then five small figures set into stones in the floor glinted at me. Four of them were dressed in the clothes or armour of their time and one depicted a former priest, Sir Thomas Cardiff who was in post from 1460-1415. In fact Kent has the largest number of remaining monumental brasses depicting the human form than any other county. These total 400. But one in particular caught my eye. How could I resist its smiling, gleeful face?

A knight in full armour, St John’s the Evangelist, Margate. ©Carole Tyrrell

Monumental brass of a priest in his vestments, Sir Thomas St John’s the Evangelist, Margate.©Carole Tyrrell

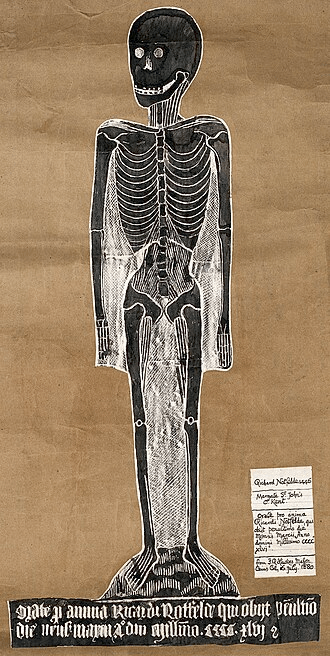

View of skeleton showing depiction of bones.©Carole Tyrrell

It was a skeleton, standing upright and tall with its arms at its sides facing the viewer, and a label underneath in Latin. This was the language of the church pre-Reformation.

The inscription reads:

‘Orate pro anima Ricardi Notfelde qui obiit penultimo die mensis marcii anno domini millesimo ccccxlvi.’

which translates as:

‘Pray for the soul of Richard Notfelde, who died on the last day of March 1446 AD‘

The skeleton’s creator has some knowledge of anatomy as the ribs have been sketched in and there are also leg and arm bones. There is a rubbing of the brass in the Wellcome Collection that dates from 1880 and depicts the bones much more clearly.

Wellcome Collection rubbing of the skeleton. Shared under Wiki Commons Brass rubbing by F.Q. Hawkes Mason, 1880.

But it was its face that caught my attention. That grin! The little eyes and nose! It’s obviously not intended to resemble a proper skull but the effect was impressive. As the brasses are in such a dark place within the church, when I stood over the skeleton to take my photos, my shadow fell on it and the grin would disappear. So it was quite difficult to take a decent picture of any of the brasses.

The skeleton is a memento mori which derives from the Latin, ‘remember you must die.’ It is intended to remind the viewer that the skeleton is all that will remain of them after death. Rich or poor, high or low, all will be the same.

According to the guide on duty, the brasses and their labels have been moved and it’s not known where they originally were within the church. But they also have a secret. They’re not actually made of brass. Instead, they were made from a cheap alloy called ‘Latten’. The guide helpfully reminded me of Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale in which he sold fake relics to simple, innocent people to extort money from them. These included a cross made of ‘Latoum’ a cheap alloy that he pretends is made of gold.

Latten was an alloy that

‘contained varying amounts of copper, tin, zinc and lead which gave the characteristics of both brass and bronze.’ Wikipedia.

These alloys were used for monumental brasses in churches, decorative effects on borders, rivets or other metalwork details as on armour for example. They were also used for livery and pilgrim badges. Canterbury Museums have the largest collection of pilgrims badges in the UK so please follow the link to see a selection.

Pilgrim Badges – Canterbury Museums & Galleries

The skeleton was an unexpected find on a Heritage Open Day and I enjoyed making its acquaintance. A rare survivor in any church although I have seen other brasses made from Latten when visiting other Kent churches.

In this case, all that glitters is not brass!

© Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading

Latten: The Definition and Meaning