20th century headlines about the murder. © Carole Tyrrell

This is where Rev Jordan came in and he became known as the parson detective. Such was the feeling in the community that he became determined to find the murderer and bring them to justice. So he set about disproving George White’s alibi.

At the time, George had claimed to have met one of his father’s employees, Joseph Green, who he had invited him to come with him. But a few yards away from the house, George had said that he had to return home to fetch his handkerchief. As a result, he was gone at least ten minutes which would have given him enough time to put the hurdle in place for the perpetrator’s gun to rest on. Joseph attested that the hurdle had not been standing at the pantry window during the day. Afterwards they had walked to the Chequers pub and Joseph said that it was the last time he saw George that night. Joseph had added that he had seen George ‘sitting up about upon the stiles’ near the murder scene before it was dark. Even more damning was that George didn’t get the handkerchief that he had said he went back home to get as, when everyone was assembled in the house after the murder, he hadn’t got one and had to go and find one.

A gun had been found in a clover stack near William’s house about a month prior to the murder and an employee called Francis Smith had put it in the hayloft. A short time afterwards he couldn’t find it and was told by George that William had taken it away, destroyed it the stock and lock of it and thrown the barrel into a lumber room.

Rev Jordan meanwhile had preached a sermon on the matter and opened a book, asking everyone in the congregation and village to write down exactly where they were at 8pm on that fateful Sunday evening.

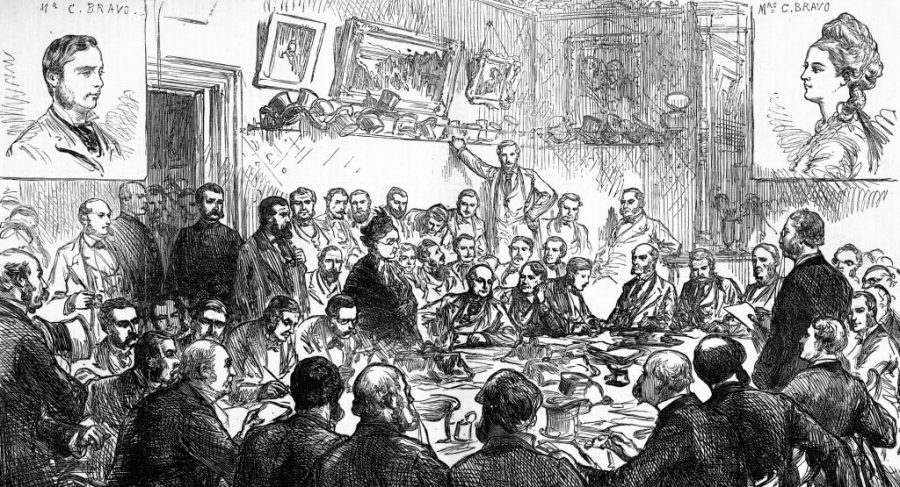

‘Rev Jordan persuaded George to make a vestry statement and a meeting was then held to clear him of suspicion. So, he stood before 40 people on Easter Monday, 3 April 1809 after a dinner at the Five Bells Inn. After the parish accounts were settled, Rev Jordan insisted that George make a public statement. He told the audience what George had said in his vestry statement and demanded that George bring in witnesses to confirm that they had seen him at any time between 7.45-8.15 to which he said that he couldn’t as he hadn’t seen anyone at that time. Some of the audience questioned him and none were satisfied with his answers.‘

The Five Bells Hoo from Facebook photographer unknown

The Rev was able to prove that George had not bought a bag of nuts at 7.45pm as a witness had said that he had seen him cracking and eating them at 7.40pm. Also, George had claimed to be standing at the Five Bells Inn when the hulks guns were fired at 8.15pm but it had actually happened at 8.00pm. He had been seen coming from the farm at 8.20pm with laboured breathing when he reached the vicarage door. He had had enough time to murder his father and then double back to the village.

So what happened next? Nothing. No one was ever charged with William’s murder and the case is still unsolved. George emigrated to Australia and that is the end of his story. There seems to be nothing more on the auction or the fate of William’s children. I could not find an image of William or of Cookham Farm House.

The only reminders are the newspaper reports in florid Victorian language such as;

‘Dastardly murder.’

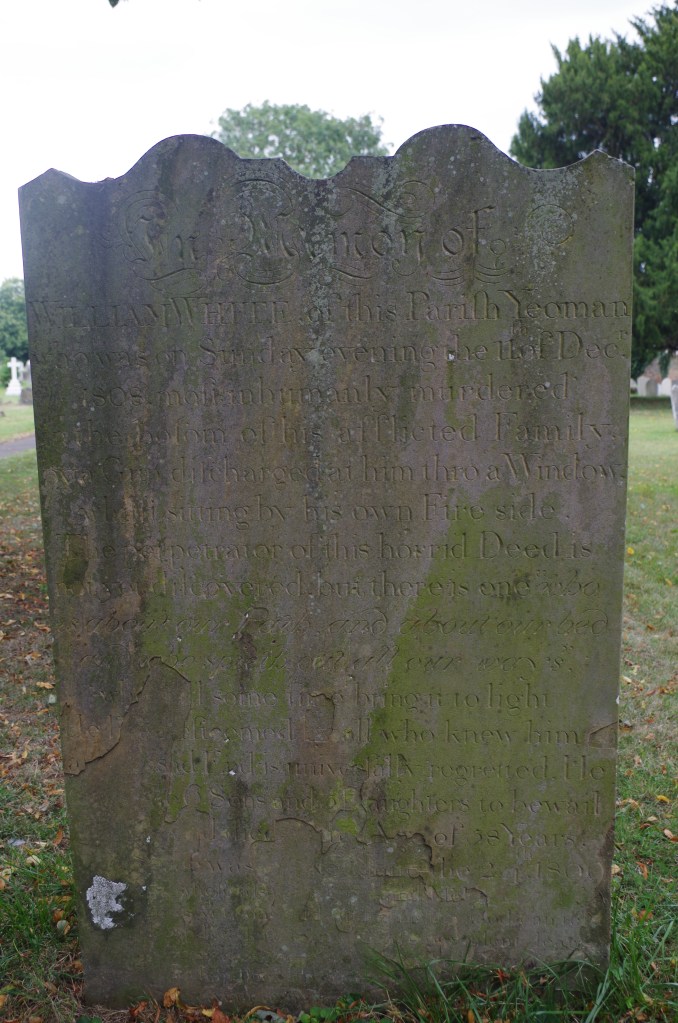

And, of course, the headstone. It’s a reminder of an event that happened over 200 years ago which shocked a community. It’s not recorded if Rev Jordan went on to do more sleuthing but I think that he made a convincing case against George. William’s grave is situated 20 yards east of the main North church door and not faraway from Thomas Aveling’s resting place.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

Aveling and Porter – Wikipedia photos of steamrollers

North Wales Gazette December 22 1808

Extracts from The Kentish Gazette

Monumental Inscriptions of St Werburgh Church, Hoo — Kent Archaeological Society

http://www.whitehousefarm.eclipse.co.uk/wwhite – a good selection of newspaper reports and Rev Jordan’s activities.

William Walter White (1751-1808) – Find a Grave Memorial

The Dastardly Murder of William – this site contains Victorian newspaper reports of the murder including 2 in London papers. Also Rev Jordan’s thought on the murder and possible perpetrators.

GRIM HISTORIES: Premeditated Murder in South East England’s Medway Towns by Janet Cameron