In light of the mass dial found at St Mary’s In the Marsh, I thought it might be timely to repeat the 2021 Symbol of the Month about them. Easily missed as they are not always where you expect to find them, they are survivors from a time where there were no time keepers such as clocks. People rose with the sun and went to bed at sunset which is why they were so important to villages and their inhabitants.

Mass Dial set into a wall at St James’s, Cooling, Kent. © Carole Tyrrell

Despite the somewhat dispiriting summer, I was determined to escape from the house and see at least one or two local churches. My little part of Kent is known as Charles Dickens country (I’m not sure that he knows about this) and there are several buildings and churches associated with him.

One of these is St James’s church at Cooling. Although closed for services, it is still kept open by local people on most days. The Churches Conservation Trust take care of it and it’s in an isolated spot which borders onto marshes. It’s also a fair walk from the nearest town, Cliffe. I didn’t see any signs of much of a village there although there is a 14th century ruined castle nearby. St James’s is the end of a terrace of houses appropriately named Dickens Walk.

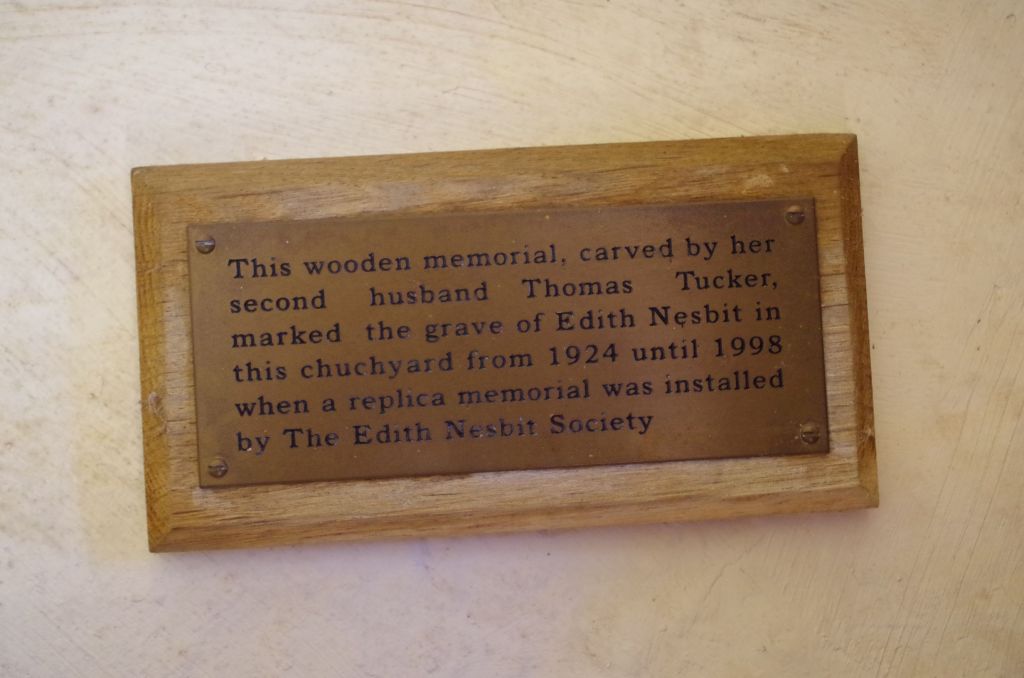

l’ll talk more about St James in a later post as it inspired one of Dickens most atmospheric scenes in ‘Great Expectations’ with the childrens graves in the churchyard. But while I was there, I found a symbol set within a wall that I had heard of but had never previously seen an example – this was the Mass Dial. I have to admit that if it hadn’t been pointed out on a display board within the church that I might have missed it as it’s set into an outer wall of the church. Not many have survived and Victorian restoration may have meant that they are found in odd places.

Mass dials are rare survivors and were a way of telling time before the invention of mechanised clocks and timepieces in the 14th century.

It was the Anglo-Saxons who established the dials. There had been confusion with all the different calendar systems such as the Lunar and Julian, and with a largely illiterate population, a visual way of telling the time was necessary.

It was the Anglo-Saxons who established the dials. There had been confusion with all the different calendar systems such as the Lunar and Julian, and with a largely illiterate population, a visual way of telling the time was necessary.

According to the Building Conservation website:

‘the Anglo Saxons divided night and day into 8 artificial divisions known in Old English as Tid or Tides. The 4 daylight divisions were called:

Morgen – 6am – 9am

Undern – 9am to noon

Middaeg – Noon to 3pm

Geletendoeg – 3pm to 6pm.

Morning, noon and evening are still in use as the last remnants of this division still in use today as are moontide, yuletide and shrovetide.’

But, throughout the Middle Ages, the Catholic church emphasised the reciting of prayers and fixed times during the day as pre-Reformation Britain was still a Catholic country. These were known as the Divine Offices and were:

Matins – pre-dawn

Prime (6am)

Terce (9am)

Sext (12pm)

None (3pm)

Vespers (sunset

Nocturnes (after sunset)

However, these were not set as the sun might not shine for a few days and if a mistake was made then the parish priest might end up celebrating certain feasts on different days from a neighbouring parish.

Mass Dial, St John’s church, Devizes, Wiltshire – note that it still has the marker in it showing how it worked.© Brian Robert Marshall under Geograph Creative Commons Licence.

They were a form of medieval sun dial and originally the hole in the centre of the dial would have contained a horizontal wooden or metal rod that cast a shadow. This was known as a ‘gnomon’ which is pronounced as No Mon. These may well have been the local community’s only way of telling the time although medieval life revolved around getting up at sunrise and going to bed at sunset.

According to the British Sundial Society,

‘mass dials can be found on the south side of many churches. They are usually small and often located on the walls, buttresses, windows and doorways of a church. However, they can also appear in more unlikely places such as inside churches and on north walls where the sun rarely shines. But they have also been found in porches suggesting that the porch was built sometime after the dial was made.’

The Society goes onto suggest that this may be

‘due to the stone blocks having been re-used in the rebuilding of the church.’

The location of the Cooling one may indicate that it’s been moved.

Again, according to Building Conservation:

‘if a mass dial is found anywhere other than a church and other than the south elevation of a church, this usually means that it has been moved from its original location often as part of a Victorian restoration. In such cases, the dials were sometimes rebuilt into the fabric upside down, making them unreadable.’

The positioning of mass dials is important and can vary. They may be on the smooth cornerstone or quoin of a tower, nave or chancel, above a porch or on a door or window jamb. Often they are set at eye level and in one church it is cut into a window ledge.

Mass dial, All Saints.Oaksey, Wiltshire. © Brian Robert Marshall. Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

Mass Dial, St Michael & All Angels., Heydon, Lincs. ©Richard Croft. Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

Mass dials also vary in their design as:

‘Some have either a few or many radiating lines, {others} have ‘hour’ lines within the circles or semi circles and others are constructed with a ring of ‘pock’ marks drilled into the stone.’

British Sundial Society

There are also variants in the way that the hour lines are numbered as they may have Roman numerals or even Arabic ones. They’re also known as scratch dials as

‘many are quite crudely scratched into the stone.’ British Sundial Society

A full circle version, All Saints, Yatesbury. ©Brian Robert Marshall Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

The 14th century brought mechanical clocks that created a regulated 24 hour time period. As a result, medieval life changed as it was no longer so reliant on daylight. However, mass dials were still in use but now they were a complete circle with lines radiating from the central gnomon to simulate the 24 hour clock. But by the 16th century they had fallen out of use. Sundials and mechanical locks had overtaken them and it was no longer the Roman Catholic church that dominated after the Reformation.

Mass dials are of great archaeological and historic importance. However, many of them are now indecipherable due to erosion and vandalism and people may not even realise what they are or their significance.

© Carole Tyrrell Text and photos unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading

https://sundialsoc.org.uk/dials_menu/mass-dials/

https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/mass-dials/mass-dials.htm

http://massdials.org.uk/links.htm