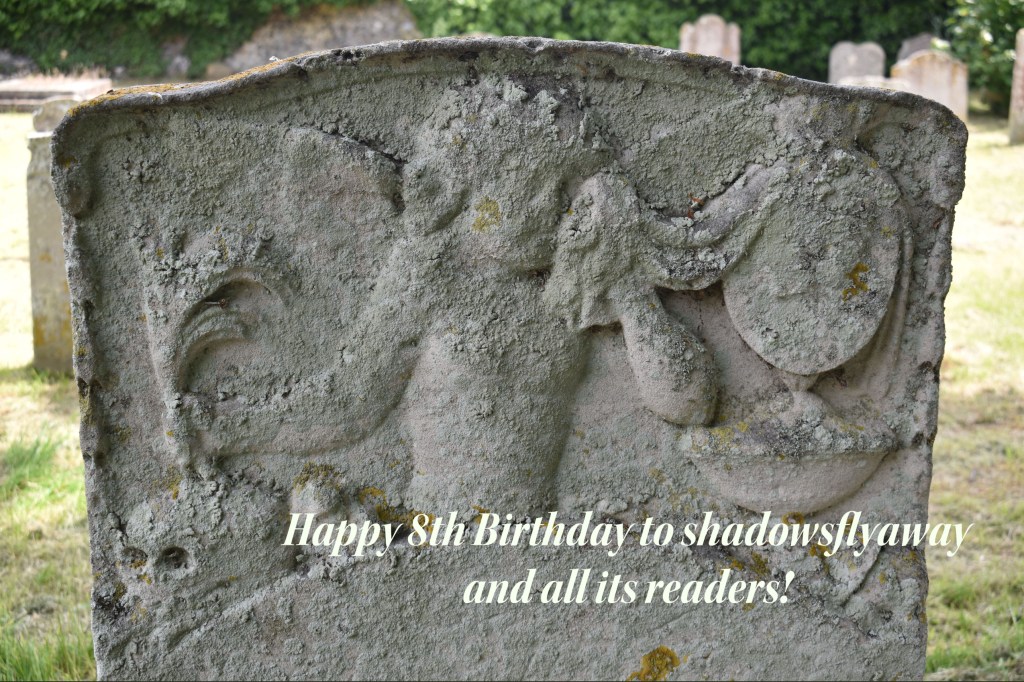

It was while exploring Beckenham cemetery in south east London that I first came across the Crown. It has several possible meanings with the most obvious one being that it symbolises victory or triumph over death. Julian Litten, an expert on cemeteries, has written that it is ‘The Crown of Life’ and a reward for those who stayed faithful until death. There are three Biblical references which support this view:

James 1:12 New International Version (NIV)

‘Blessed is the one who perseveres under trial because, having stood the test, that person will receive the crown of life that the Lord has promised to those who love him.’ https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=James%201:12

and also Revelation 2 10 and Corinthians 24:27

However, from the earliest it has been seen as a symbol of leadership, distinction and royalty. A variety of saints also wore crowns to indicate that they were either a martyr or of royal blood and there is a 19th century painting by Robert Bayne dated 1864 depicting saints ‘casting down their crowns before Christ.’ The Virgin Mary is often portrayed as wearing a crown as well as in this image:

Virgin Mary and Christ baby from Pinterest.

But J C Cooper has a more esoteric interpretation and says that it is ‘an architectural emblem of the celestial world and form the point of exit from this world and entry into the divine.’

In the Jewish faith it’s known as ‘The Crown of Good Name’ which alludes to the deceased as being of ‘exceptionally noble character.’ However, it can also be a representation of the head of the family or of a household. I think that Julian Litten’s view is probably the most likely given the Biblical references. There is also another variant which is the Cross and the Crown as here in this example from the Champion headstone in Fairmount Cemetery, Colorado, US:

© Cemeteries and Cemetery Symbols (wordpress.com)

With this one, it has been suggested that the cross represents suffering and the crown is the eternal reward.

This example comes from Brompton where it is at the top of a very ornate and beautiful memorial. This is a radiate crown and, according to J C Cooper, it can represent ‘ the energy and power contained in the head which was regarded as the seat of life-soul, …an attribute of sun gods,….of supernatural people and the points of the crown symbolise the rays of the sun…’ or it may just be an attractive decorative device.

Crown of thorns:

This is a variant on the crown as it is a representation of suffering, passion and martyrdom. It’s based on the ‘crown plaited by the soldiers and imposed upon Jesus during his trial before Pontius Pilate’ according to Julian Litten. J C Cooper asserts that this was a ’parody of the Roman Emperor’s crown of roses’. The soldiers then mocked Jesus by kneeling in front of him and hailing him as ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ A potent emblem of royalty and power had been turned into one of pain and degradation. But the crown of thorns is a prelude to Jesus being given a far worthier crown in Heaven. This is confirmed in Hebrews 2:9: “

But we see Him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honour because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God He might taste death for everyone”

In a famous painting of the executed King Charles 1, the Eikon Basilike, he has abandoned his earthly crown, the symbol of majesty, for the crown of thorns that he is holding in his hand as a representation of his suffering.

Both the Crown and the Crown of thorns are deeply religious symbols and are examples of the deceased’s faith. They are also symbols, I believe of resurrection and the deceased’s belief in an afterlife which may have given comfort to those left behind. and also their belief in an everlasting life beyond the grave.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell

References:

http://www.graveaddiction.com/symbol.html

http://www.sztetl.org.pl/en/term/131,funerary-symbolism/

http://www.thecemeteryclub.com/symbols.html

http://www.undercliffecemetery.co.uk/undercliffesymbolism.pdf

http://www.lsew.org.uk/funerary-symbolism/ (Julian Litten)

https://www.gotquestions.org/crown-of-thorns.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eikon_Basilike

Cross and Crown | Cemeteries and Cemetery Symbols (wordpress.com)

Christian symbolism – Wikipedia

Stories in Stone; A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography, Douglas Keister, Gibbs M Smith, 2008

An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, J C Cooper, Thames & Hudson, 1978