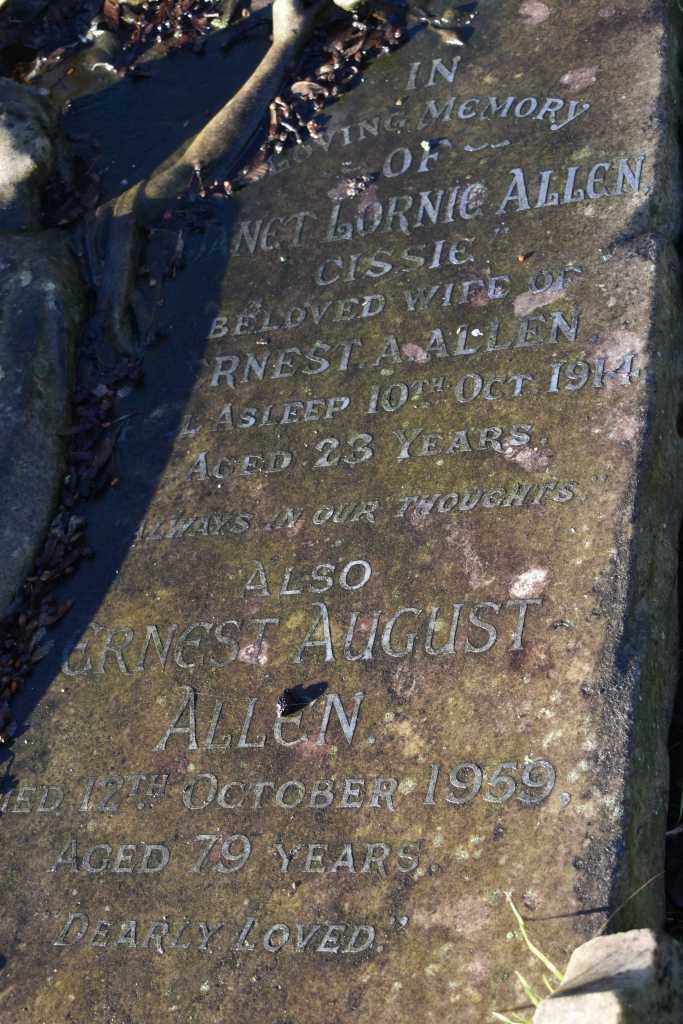

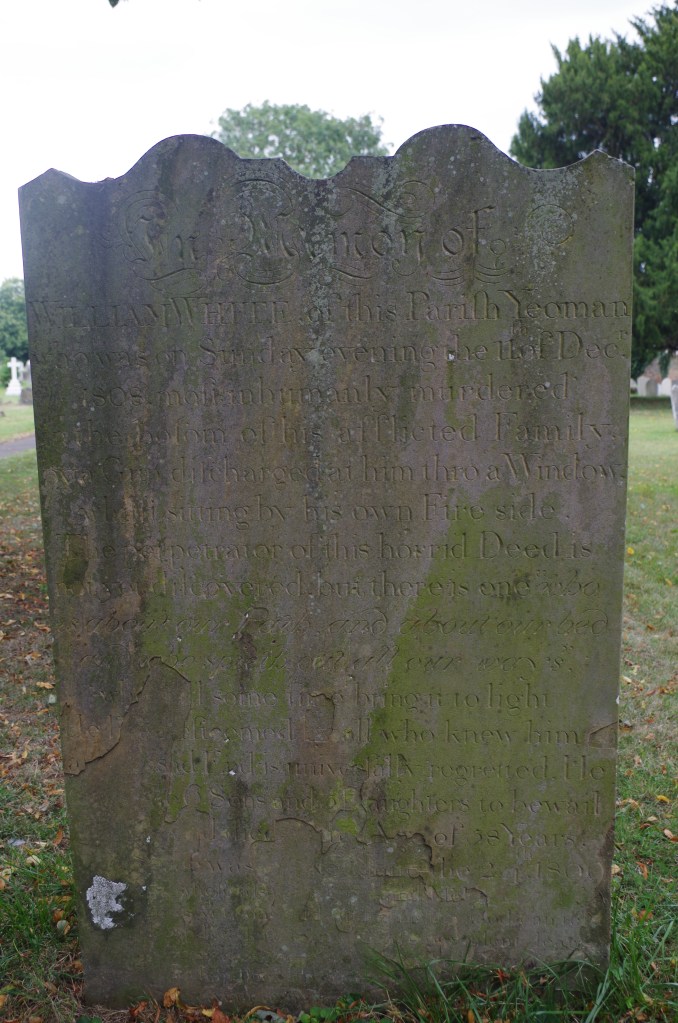

William White’s headstone and fulsome epitaph. © Carole Tyrrell

You never know what you will find in a country churchyard; crumbling mausoleums associated with royalty, a fine selection of skulls on headstones and poignant memorials.

But what I didn’t expect at Hoo was to find one that revealed, positively shouted in fact, about a local unsolved murder from the early part of the 19th century. This is the headstone dedicated to William Walter White. This is the inscription:

‘IN MEMORY OF

WILLIAM WHITE OF THIS PARISH, YEOMAN

WHO WAS ON SUNDAY EVENING THE 11TH OF DECR.

1808 MOST INHUMANLY MURDERED

IN THE BOSOM OF HIS FAMILY

BY A GUN DISCHARGED AT HIM THRO A WINDOW

WHILST SITTING BY HIS OWN FIRESIDE

THE PERPETRATOR OF THIS HORRID DEED IS

NOT YET DISCOVERED BUT THERE IS ONE, “WHO

IS ABOVE OUR PATH AND ABOUT OUR BED

AND WHO SPIETH OUT ALL OUR WAYS”

WHO[O] [WI]LL SOMETIME BRING IT TO LIGHT

HE LIVED ESTEEMED BY ALL WHO KNEW HIM

[AND HIS] SAD END IS UNIVERSALLY REGRETTED HE

[LEFT ISSUE]6 SONSAND 5 DAUGHTERS TO BEWAIL

[HIS LOSS AND DIED [AT] THE AGE OF 58 YEARS

STONE WAS ERECTED JUNE THE 24TH 1809

“[By] whose Assa[ssinating} {H}and [I fell]

[Drop] Reader [o’er my Grave one] Silent Tear

[Live Well remembering that your God is Near]

[If Rich or Poor or Relative you be]

[Strike your own breast and say – It was not Me!]’

A more dramatic epitaph it would be hard to find and the stonemason certainly earned his money! The case shocked the farming community of Hoo especially as no one was ever brought to justice and suspicions ran rife. It even led to the local vicar of St Werbergh’s at the time, Rev Jordan, deciding to become an amateur sleuth and unmask the perpetrator.

Death had already visited the White family when William’s wife, Jane, dropped dead with no prior indication of illness on 24 March 1808 aged 44. The murder left the 11 children orphans within a short space of time and more about what happened afterwards later. William was a man of some standing in the village. He was a yeoman which meant that, although he was a farmer, he wasn’t part of the gentry. In 1790, he was one of only two franchised householders in the village and so was eligible to vote.

A typical farm house in Hoo. © eclipse

The Murder

The facts are that, on Sunday 11th December 1808, William was sitting reading at home with his family when a shot rang out. A gun had been fired through an open pantry window which killed William outright. The shot entered the back of his head and exited under the right eye. The ‘cries and lamentations’ of his family could be heard in Hoo village a mile away after the body was found. An unsuccessful search was made immediately for the perpetrator. However, a recently discharged gun was found in a ditch roughly 200 yards away from the house near the River Medway which led to the assumption that the murderer had escaped by water.

Such was the notoriety of the case that reports of it appeared in London newspapers and the Bow Street Runners were called in. They were the forerunner of the modern police force.

Bow Street Runners c1800 from History UK website.

Whoever fired the fatal shot must have known the layout of the house and the family’s habits. It took place on a Sunday when there were no servants about and it would have been necessary for the pantry door to be open in order to have a good view from the window as the gun was fired at William sitting by the fire. It had been propped up on a hurdle in front of the window and this helped the murderer to have a good aim. The gun was an old musket-barrel which had nails in the breach fastening it to the stock. It was a very crude gun as the hammer would not hold at full cock but was fastened back by a piece of twine which was presumed to have been cut at the time of firing. The fatal shot was fired at the same as the nightly salvo of guns from convict hulks on the River Medway.

The suspects

The gun’s owner was a man called Driver and he and another man called Day were picked up in Bapchild near Sittingbourne, Kent. It was assumed that they were on the run. The Coroner, J Simmons Esq, questioned them but soon realised that he didn’t have enough evidence to prosecute them. He then had them removed to one of his Majesty’s ships which was a euphemism for being ‘press ganged’. The Kentish Gazette described it like this:

‘as they were unable to give a satisfactory account of their mode of obtaining a livelihood, they were sent to serve their country on board one of his Majesty’s ships of war.’

If that wasn’t enough, later on, they were marched back from Portsmouth to Rochester to be further questioned and then press ganged a second time before being finally released without charge.

As for motive, William had recently found a servant, possibly Driver, in the act of robbing a neighbour and had informed the appropriate authorities. He had sacked the man who had sworn to get his revenge. In fact, a week prior to the murder, the unnamed man, had purchased a gun:

‘for which he had no possible occasion, under some frivolous pretence’

according to newspaper reports at the time.

The inquest on William was held and a verdict was returned of:

‘Wilful murder against some per or persons unknown – Friday 23 December 1808.

Events began to gather pace as the executor of William’s will, Thomas Denton, was authorised to put William’s home, land, possessions and other assets up for auction. It was intended that the money raised would be distributed by him amongst the children as he thought best for them. Originally it had been intended that Jane White, William’s wife would be a joint executor but of course with her death it fell to Thomas alone. Understandably the children tried to stop him and suspicion began to fall on him. In the space of a few months they had been left orphans with the loss of both their parents and now they were to lose the family home as well.

But another suspect had appeared who was much closer to home. It was George White, William’s eldest son. He was known to be on bad terms with his father and had been seen to threaten him. George wanted the farm and the land but William was considering writing a new will leaving him and another relative out. However, his will dated 22 January 1808 did not indicate.

But George had convinced both the Mr Simmons, the coroner, and the Bow Street Runners that, during the vital thirty minutes between 7.45pm and 8.15pm he had been in Hoo village buying:

‘a penny’s worth of nuts.’

The shop was a good mile away from the farm. But someone else in the community had doubts about George’s alibi and was determined to disprove it as we shall see in Part 3.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

Part 3 – the parson detective comes onto the scene