It was a dark, gloomy grey Sunday when I decided to explore the cemetery and walked up the impressive avenue of yew trees studded with bright red berries to the two cemetery chapels. But, by the entrance, I discovered a smaller building hidden behind bushes in the Gothic style of the chapels. I thought that it might have been a mortuary chapel but, on looking at the map, it may have been a more prosaic toilet block now locked up. The cemetery is officially known as St John’s cemetery and also houses a crematorium and associated gardens of rest.

After the excitement of Halloween, people appeared to have donated their pumpkins to the local wildlife and I disturbed a squirrel scampering over one. However, although people may consider them to be a tasty treat. Forestry England doesn’t agree and suggests on their website that they be reused to make pumpkin soup or be added to compost.

Nothing prepared me for the size of the cemetery and, so far, I have been unable to discover its exact dimensions. I soon realised knew another visit or two would be necessary to explore it fully. The bright Autumn colours of the leaves were dulled by the greyness of the skies as I merrily kicked up leaves and looked for fungi. But all I could find were a couple of what I thought were parasol mushrooms lurking in the fallen leaves.

Presumed Parasol fungi in autumn leaves ©Carole Tyrrell

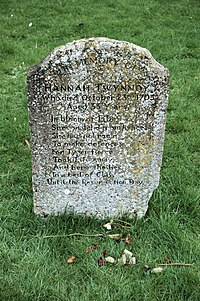

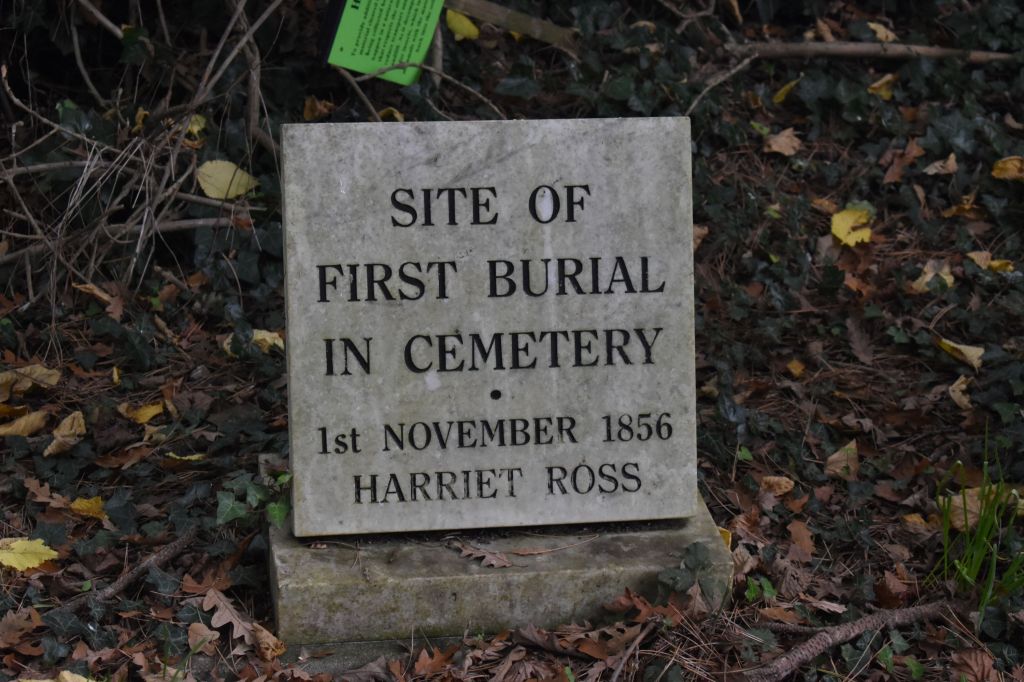

Placemarker of first burial ©Carole Tyrrell

The cemetery was opened in 1856 and a sign marks the place of the first burial which was a woman, Harriet Ross, on 1 November of that year. Most of the first section along the main avenue dates from the 19th century. As I neared the chapels, there was a large monument in a gap between the yew trees, set back from the path featuring an angel praying before a cross with, I assumed, a portrait of the deceased looking approvingly on. This was on the LeMair monument.

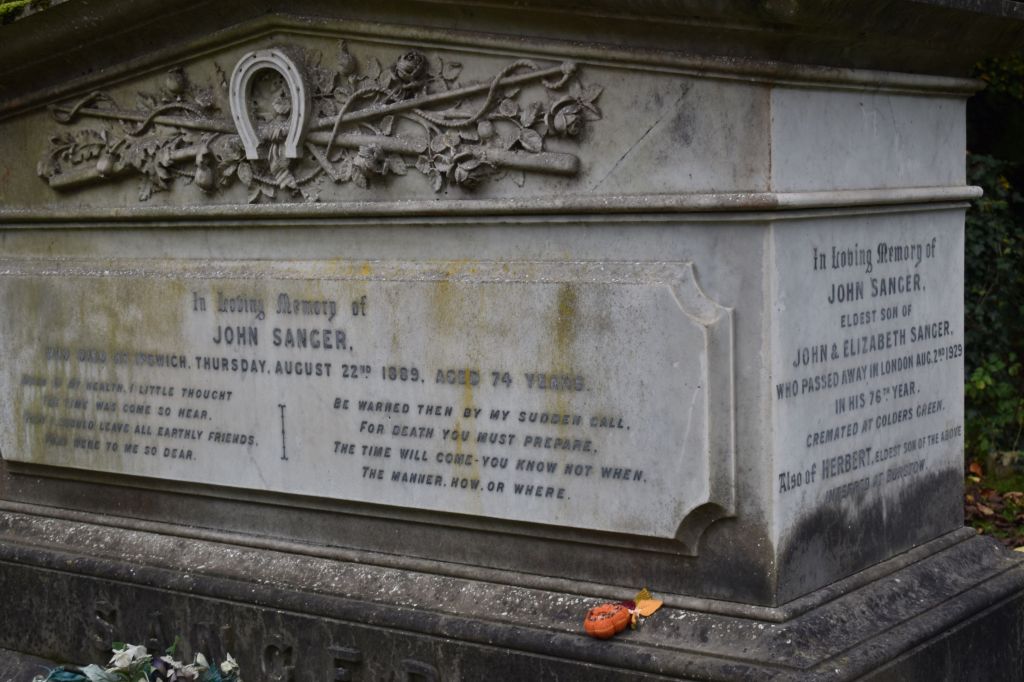

A sign announced ‘Sanger Path’, I wandered along it and came to my first surprise of the day. 4 angels forming a square, one at each corner, on the Reeve memorial. They are well sculpted with detail on the back as well. But then my eye was drawn, well I could hardly miss it, by the lifesize statue of a horse atop the Sanger monument. Beautifully sculpted, it is dedicated to a circus proprietor, John Sanger (1816-1899). He has a tenuous connection to one of my favourite Beatles songs. There is an upturned horseshoe above John Sanger’s epitaph for luck and his shows featured equestrian acts involving horses and ponies and a pantomime every Christmas. He originally went into partnership with his brother, George, but eventually they went their separate ways. George was brutally murdered in 1911 by an ex employee who then committed suicide. A photo album of George’s circus, its performers and animals came up for auction in 2017 and showed that a Victorian circus certainly was value for money! The Sanger circus appeared by royal command at Windsor Castle by Queen Victoria and they also took part in the annual extravaganzas at Crystal Palace.

The Sanger horse ©Carole Tyrrell

©Carole Tyrrell

One of George Sanger’s great granddaughters ashes are also interred in the family plot. This was Victoria Sanger Freeman (1895-1991) and she went under the sobriquet of ‘Queen of the Elephants’ with 4 of them under her charge. She was the last member of the Singer dynasty of circus performers. Beside John Sanger’s horse is another Sanger, Mary Rebecca, who married into the family. She is sandwiched between John and the Reeve ladies. She married William Sanger but I’m not sure at the moment where he stood within the Sanger hierarchy.

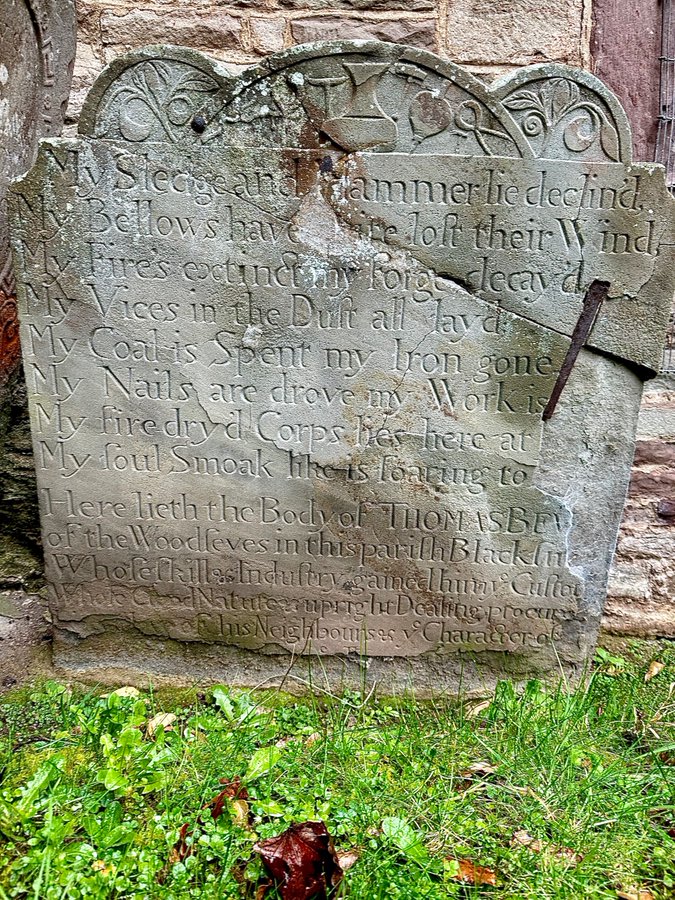

There was an interesting variation regarding epitaphs within the cemetery. On several graves, they were carved within an oval frame that was reminiscent of a portrait. I thought they looked very elegant.

There was only one way to discover why another path was named ‘Surfboat Path’ and halfway down I came upon the Grade II listed memorial to the Surfboat Disaster. It commemorated the tragedy that killed 9 Margate boatman on 2 December 1887 and was restored by the Royal National Lifeboat Institute, 120 years later in 2017.

The town’s surfboat, ‘Friend to All Nations’, went out on that night in appalling weather to assist the sailing vessel, ‘Persian Empire’. Sadly, the surfboat capsized on the Nayland Rock in Margate with only 4 survivors. A surfboat is according to Wikipedia:

‘A surfboat (or surf boat) is an oar-driven boat designed to enter the ocean from the beach in heavy surf or severe waves. It is often used in lifesaving or rescue missions where the most expedient access to victims is directly from the beach’

The 2017 memorial service was not only to acknowledge the tragic event but also as a reminder that the crews and elements still face the same challenges as emphasised in the sad loss of the crew of the Penless lifeboat in 1981. To say that it is impressive is an understatement as it is surrounded by more modest memorials. It’s in the shape of a huge rock with a lifesize mourning woman, her hands to her head, face turned away, in Victorian dress and carrying a laurel wreath, an evergreen that symbolises eternity. There is an epitaph to the disaster beside her and above, on the top of the rock, are a collection of nautical symbols: chains, anchors, ropes and a life belt with the surfboat’s name on it. I was stunned although I would have expected a few nautical graves due to Margate being on the coast.

Part 2 – A doomed air flight, an unusual angel and an art lover’s final resting place

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated

References and further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Sanger_Freeman

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surfboat

https://courtauld.ac.uk/about-us/our-history/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Courtauld_(art_collector)

https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Sanger

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Sanger

https://theisleofthanetnews.com/2017/12/15/a-service-has-marked-the-restoration-of-margates-surf-boat-memorial-and-the-loss-of-9-lives-in-the-tragedy/

https://margatelocalhistory.co.uk/Pictures/Pictures-Storms.html

https://theisleofthanetnews.com/2017/10/04/rare-collection-of-lord-george-sanger-circus-photos-sold-at-auction/

https://daily.jstor.org/vintage-circus-photos-sanger-circus-collection/

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/46295073/edmund_leonard_george-betts

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1396419