View of the church along the churchyard path.©Carole Tyrrell

It was a glorious Easter Saturday this year and so I thought I’d go for a springtime walk in the Kent countryside near my home. On an earlier visit to St Mildred’s in Nurstead near Meopham in 2019, a local man had recommended visiting Ifield church which was just ‘a mile down the road’. I assumed he meant ‘a country mile’ which may not be the standard length of a mile as we know it. I travelled to Meopham by train and then put my trust in Google maps. I was feeling lucky that day…

Esater bunnies in St Mildred’s churchyard, Nurstead. ©Carole Tyrrell

Daffodils in St Mildred’s churchyard, Nurstead. ©Carole Tyrrell

As I sat in St Mildred’s churchyard I saw real easter bunnies pottering about who then adroitly vanished when they realised that a human was about. ‘Very wise.’ I thought and then set off to Ifield. The local ‘big house’ is Nurstead Manor which is across the road from St Mildred’s and it is surrounded by fields with some magnificent horses in them. St Mildred’s was closed but spring flowers were in the churchyard. Daffodils seemed to burst forth on one grave and there were patches of wild violets, purple and white. Spring was in full swing. Due to the lack of street signs, I hoped that I was on the right road when I took a left hand turn and walked on until I saw a sign. Along the road, on the verges, there were great patches of Lesser Celandine which is one of the seven signs of Spring.

Lesser Celandine on a roadside verge. ©Carole Tyrrell

As I stood there wondering in what direction I should be going as there was no sign of a church, a passer by advised me to follow the signs to the lambing farm 100 yards ahead.

©Carole Tyrrell

©Carole Tyrrell

©Carole Tyrrell

Intrigued, I did so and, after paying £4, I was directed to a shed in which there was an assortment of lambs and ewes in pens. Some of the lambs were only 2 days old and others were playful, climbing onto their mum’s thick woolly coats or having a kip. But they were not destined for Sunday lunch as they were a rare breed, the Cobham Longwool, of which there are only 500 in the country. ‘So not for eating.’ the farmers wife comfortingly told another visitor which was a relief. I had held a lamb and felt a little guilty. We were also shown their two pigs who were very lively and, after a pizza and being given directions, ‘It’s quite a way further on.’ I resumed my walk. One of her companions said as I moved on, ‘Oh she’s one of those people who like visiting churches, they’ll walk miles to see one.’

They weren’t kidding. The road was empty, devoid of houses and cars and other walkers. It seemed strange to have a church so far out of town but I have become accustomed to isolated churches in North Kent. Ifield is recorded in the Domesday 1086 and is a hamlet of only 12 houses with no sign of any shops and St Margaret’s is at the very end. Unknowingly I was on the ancient village street, Ifield Street, which was an isolated empty road and unlit at night. I can’t imagine too many late night services being held there during winter.

View over the fields from the churchyard. ©Carole Tyrrell

View of church from churchyard. ©Carole Tyrrell

Despite the website saying it was open daily, on my visit it was closed, which seemed odd at Easter. So, I was unable to see the interior and the remaining medieval features. The nave and chancel date from the 13th century and there is a 12th century font. It’s a quiet location although I could hear the endless traffic on the A2 that separate the church from the hamlet. Its rough stone walls are now covered by modern cement which makes it look younger than it actually is and gave it, in my opinion, a slightly American look. In fact St Margaret’s is known by the locals as the ‘Little church on the Prairie and I could see why as it’s surrounded by fields which contained tall yellow flowers which I assumed were rapeseed. By now the fields would be a bright acid yellow. Quite a sight to see.It is thought that Chaucer’s pilgrims on their way to Canterbury would have passed by the church, and standing here in this isolated spot I could believe that the landscape might not have changed much.

War memorial just outside the lychgate.©Carole Tyrrell

Names inscribed on the memorial from the First World War. ©Carole Tyrrell

The impressive War Memorial just outside the lychgate dates from 1919 and originally commemorated the village’s fallen of the First World War. There was

‘ a service of dedication for the memorial on 20th June 1919 which was a week prior to the end of the First World War with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.’

It’s built of Cornish silver-grey granite and cost £120 at the time which was raised through subscriptions from parishioners. Names from the Second World War are also inscribed on it and a full list of names is on the www.ifieldparish.org website.

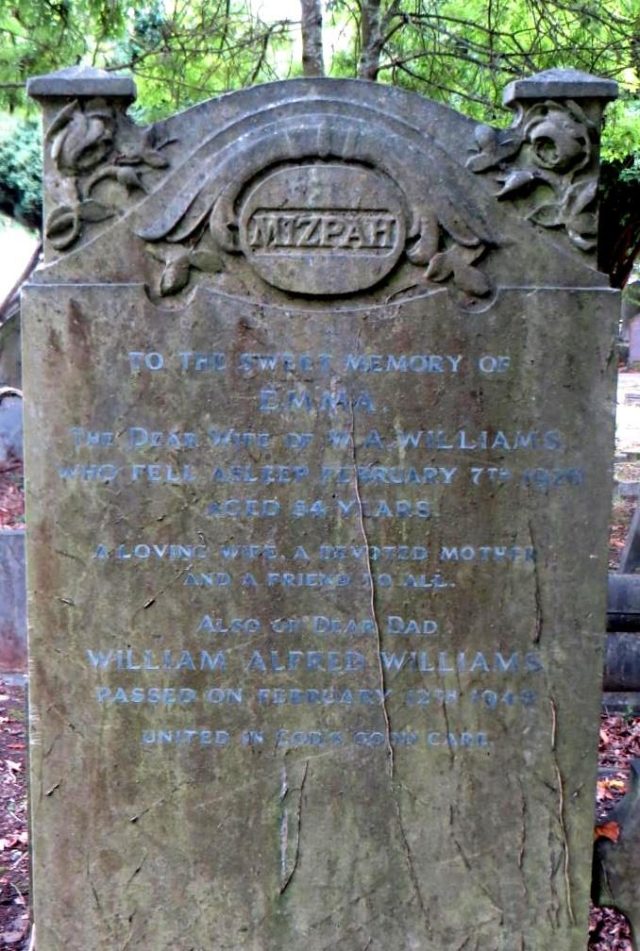

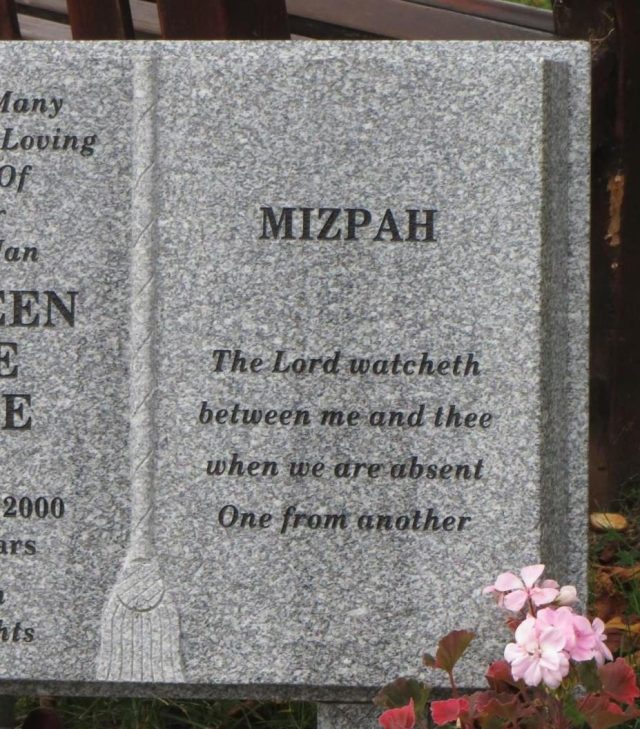

The churchyard contains mostly 19th, 20th and 21st memorials and was a symphony in yellow. Dandelions abounded and these can be seen as symbols of astral bodies. The flowerhead in full bloom is emblematic of the sun, the dandelion clock is the moon and the scattering seedheads are the stars. Lesser celandine was still there in abundance and near the lychgate there was a small patch of cowslips. I also saw tulips and grape hyacinths.

More Lesser celandine swarming over the churchyard.©Carole Tyrrell

A patch of dandelions. ©Carole Tyrrell

Grape hyacinths. ©Carole Tyrrell

Cowslips. ©Carole Tyrrell

More cowslips. ©Carole Tyrrell

There were a sprinkling of 18th headstones on which pairs of winged messengers and also an impressive winged skull could be seen.

18th century headstone showing winged messengers. ©Carole Tyrrell

18th century winged skull on a headstone. ©Carole Tyrrell

On this one, it can be seen very clearly what the departed’s hobbies or occupation was. A clear example of ‘the tools of the trade’. And there was an unusual cast iron memorial to ‘our two sons’ on one headstone.

©Carole Tyrrell

©Carole Tyrrell

©Carole Tyrrell

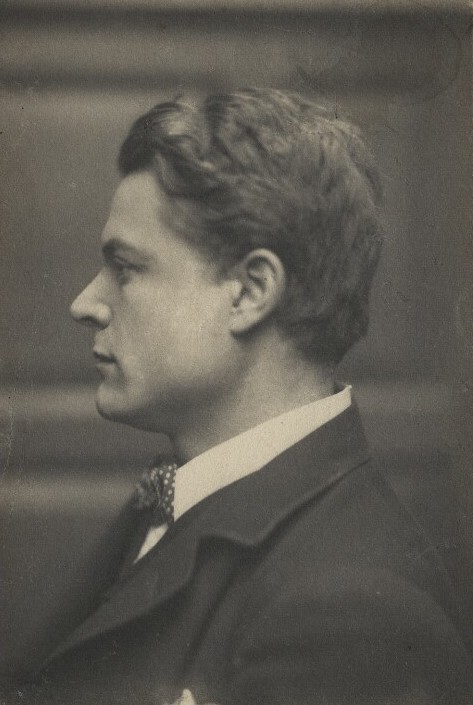

This is the largest and most significant group of memorials and commemorates the Colyer Fergusson family who were associated with Ightham Mote, now a National Trust property. It’s a

‘medieval moated manor house roughly 7 miles from Sevenoaks’ according to the National Trust website. Thomas Colyer-Fergusson, eventually to assume the title of ‘Sir’ when he assumed the additional name of Colyer in 1890 and his bride, Beatrice, set up home at Ightham in 1889 and were keen to make their mark on the house. They were very forward thinking and introduced:

‘central heating, electricity and bathrooms connected to the mains water supply.’ Ightham Mote | Kent | National Trust

These amenities were undoubtedly appreciated by their retinue of indoor servants and gardeners. In addition, the Colyer-Fergussons introduced the opening of rooms to visitors on one afternoon a week for the price of 2 shillings. Octavia Hill, one of the founders of the National Trust was a visitor.

But the carnage and of the 2 World wars badly affected the Colyer-Fergussons. In the first World War, Thomas’s second son, Billy suffered shell shock and the youngest son, Riversdale was killed at Ypres aged 21. Riverdale’s death had a profound effect on Thomas in that he would not allow the gardeners to

‘make any changes to the garden, asking them not to cut back any plants or remove dying trees.’

Ightham Mote | Kent | National Trust

During the Second World War, Max, Thomas’s eldest son, was killed in a bombing raid on an Army training school in 1940.

Thomas died in 1951 and Ightham Mote was inherited by Max’s son, James. He had no children and was only too well aware of the huge expense that would be incurred in maintaining the house. So he sold it and its contents leaving it with an uncertain future and eventually it was taken over by the National Trust. The baronetcy became extinct with the death of the 4th Baronet in 2004.

There is an obituary on the Kent Archaeological Society website to Sir Thomas in which he is thanked for his ‘patient and persistent work’ in transcribing parish registers. This was no mean task as they were largely handwritten and not indexed. He was very involved with the Society and eventually became its Vice-President.

©Carole Tyrrell

The last Baronet, after this the title died out. ©Carole Tyrrell

And so here the Colley-Fergussons rest in this serene churchyard surrounded by the other departed villagers and parishioners and the Spring flowers that indicate Mother Nature is returning to life. It was interesting to see a connection between Ifield and Ightham Mote as the house is one of my favourite places to visit and I based a short story on a particular painting on display there.

I retraced my steps back to Meopham and St Mildred’s churchyard resisting the urge to ask any passing horse and rider a lift for some of the way. The clip clopping of horses hooves had let me know that there was an equestrian establishment close by. Already the long shadows of the early evening were racing over the fields but it had felt so wonderful to be outside and exploring once again after a long winter.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading

History of St. Margaret’s Church | Parish of Ifield (ifieldparish.org)

Ifield St Margaret of Antioch | National Churches Trust

Ightham Mote | Kent | National Trust