View of the D’Este Mausoleum showing bricked up entrance. ©Carole Tyrrell

Part 1 – The love story and a terrible home coming

The churchyard of St Lawrence in Ramsgate contains 1400 graves and was consecrated in 1275. It is now closed to burials but as I explored in early October I found a huge mausoleum right at the very back, peeping out from behind yew trees. It is a little worse for wear to say the least but the mausoleum has royal connections.

It is the D’Este mausoleum according to an information board and the guidebook. Its inscriptions are now illegible, the outer decoration has been smashed, its roof tiles stolen and the entrance has been bricked up but it has such a story to tell.

It contains 6 people hence its size. They are:

The Duchess of Sussex, wife of Prince Augustus Frederick.

The Duchess’s parents, the Earl and Countess of Dunmore

Two unacknowledged grandchildren of King George III, Augustus and Augusta. She is interred with her husband, Sir Thomas Wilde, The Lord High Chancellor.

Illustrious permanent residents indeed. I was immediately intrigued and found an archive photo which showed that it had once had an imposing position within the churchyard. Please follow this link:

MMT – Gazetteer Mausoleum Details

It is now considered to be at risk.

The D’Este Mausoleum showing where the inscriptions would have been originally on all sides of the mausoleum. ©Carole Tyrrell

This is the original wording on the inscriptions from 1895:

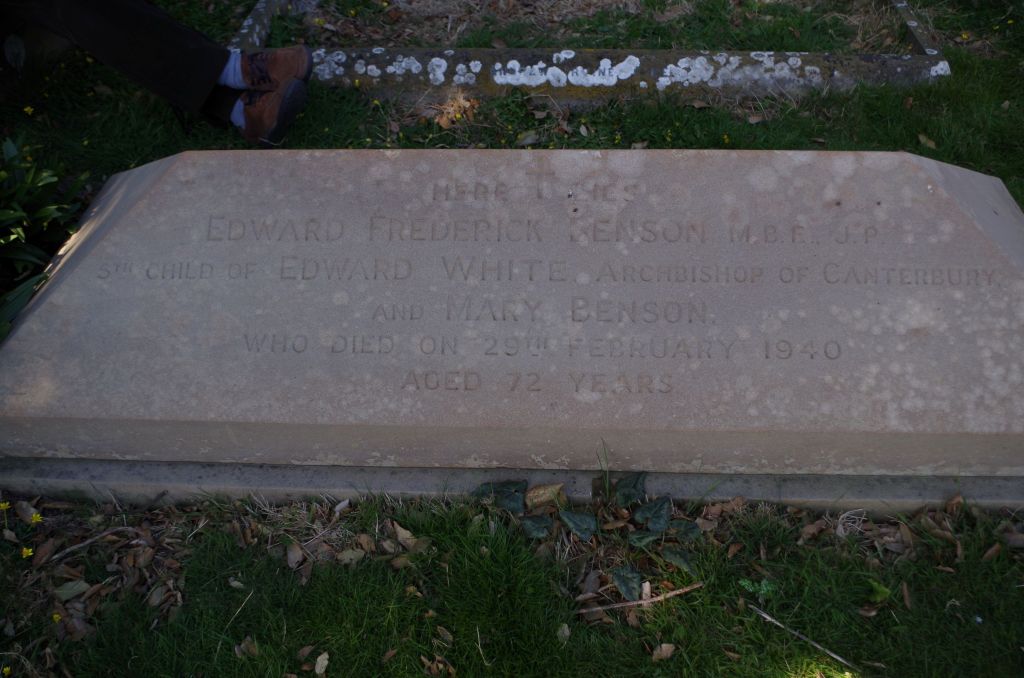

324. D’Este Mausoleum. South side: Sacred to the beloved memory of The Right Honorable Thomas WILDE, 1st Baron TRURO, who began his professional life as an attorney, by great talent, perseverance, and integrity, unaided by patronage, became Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, and afterwards Lord High Chancellor of England. Born 7th day of July 1782, died 11th November 1855. He had by his first marriage with Mary WILEMAR three sons, the eldest of whom died in infancy, and one daughter. By his second wife Augusta Emma D’ESTE he left no issue. In this tomb are also enclosed the remains of The Right Honourable Augusta Emma, Baroness Truro, widow of Thomas, 1st Baron Truro. And only daughter of Augustus Frederick, Duke of SUSSEX, who died on the 21st day of May 1866. “May God mercifully receive her soul”.

On the west side of ditto: Erected by Augustus Frederick D’ESTE, to receive the mortal remains of his venerated and loved mother, the Lady Augusta MURRAY, 2nd daughter of John, Earl of DUNMORE. Married at Rome on the 4th day of April, A.D. 1793, to His Royal Highness, Prince Augustus Frederick, afterwards Duke of SUSSEX, 6th son of His Majesty KING GEORGE THE THIRD, a subsequent marriage was solemnized at St George’s Church, Hanover Square, London. Both marriages were held invalid in England, as contrary to an Act of Parliament entitled “The Royal Marriage Act”. Here also repose the remains of Augustus Frederick D’Este, the only son of Lady Augusta, and His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex. Born 13th January 1794, died 18th December 1848.

North side of ditto: On this side are deposited the remains of John, 4th Earl of DUNMORE, died March 1809, and of his Countess, the Lady Charlotte STEWART, daughter of Alexander, 6th Earl of CALLAWAY, died November 1818.’ Kent Archaeological Society

Lady Augusta Murray – portrait miniature by Richard Cosway. Image shared under Wiki Commons

It’s the inscription to Augusta, Duchess of Sussex that begins the story. This is the 18th century Royal marriage which fell foul of a punitive Act of Parliament, The Royal Marriages Act. A wife was denied and repudiated becoming a social outcast, her family ruined and her children nameless. Until eventually she ended up living in Ramsgate where several road and street names still commemorate her. This the sad story of Lady Augusta Murray’s doomed marriage to Prince Augustus Frederick, the sixth son of George III.

I am indebted to Julia Abel Smith’s biography of Lady Augusta, ‘Forbidden Wife – the Life and Trials of Lady Augusta Murray’ which was published by The History Press in 2020.

She was the daughter of John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore and his wife Lady Charlotte Stewart. Augusta was 32 when she met Prince Augustus, the sixth son of George III in Rome in 1793 . He was 20 and largely estranged from his father. She was widely travelled and very accomplished which was unusual for a woman of her time. Her father had been the Governor of New York, and later Virginia, as the first stirrings of independence happened. In fact, she and her mother were in Gibraltar when news came of the French Revolution and the beheading of Marie Antoinette. Augusta and Augustus then remarried in London.

Prince Augustus Frederick, portrait by Guy Head. Shared under Wiki Commons.

Augustus had not yet told his father of the marriages as he wanted to do it when he became of age. But neither he nor Augusta had any idea of how strictly the Royal Marriages Act of 1771 could be applied, and particularly to them, once George III and Queen Charlotte found out.

The Act declared that any descendants of George III would be prevented from marrying without his previous consent as well as his heirs and successors. Any marriage contracted without the King’s consent would be null and void. The result of this would be ruin and rejection for both parties and any children would be illegitimate. Anyone connected with the marriage would also be liable for prosecution. However, it was different if the royal petitioner was aged over 25 and hadn’t received the King’s consent as they could give notice to the Privy Council and, if within a year the Houses of Parliament had no objection they would be free to marry.

The inquiry on the legitimacy of both of the marriages which was held on 27 January 1794, was scathing. The marriages were deemed ‘pretended’ and ‘absolutely null and void’ and Augusta was ‘falsely calling herself the wife of the said Royal Highness Prince Augustus Frederick.’ If that wasn’t enough she was also liable for the legal expenses. But Augusta always regarded her marriages as completely legal.

As a result of the inquiry she was awarded a pension of £1,000 p.a. but she, their children and her family became pariahs in the eyes of polite society. But her parents never stopped supporting her.

Prince Augustus and Augusta continued to see each other and a daughter, called Augusta Emma, was born on 9 August 1801. She was always known as Emma. She and her brother were given the surname of Hanover and it was later changed to D’Este. But life was hard for Augusta with no income and no longer being part of society. She ended up in considerable debt.

However, after eight years of trying to have Augusta recognised as his wife, the final separation came on 7th December 1801 when Augustus finally conceded defeat. He wrote:

‘We are to meet no more. My whole wish now is to make her comfortable.’.

He then became the Duke of Sussex in England, Earl of Inverness in Scotland and Baron Arklow in Ireland. He also moved to Portugal and had a mistress.

Part 2 – The aftermath and the move to Ramsgate

Text and photos ©Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading:

Augusta Emma Wilde, Baroness Truro – Wikipedia the daughter

St Lawrence, Laurence, Ramsgate, Thanet – Churchyard M.I.’s by Charles Cotton 1895 the sicriptions on the Mausoleum

Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex – Wikipedia

Lady Augusta Murray – Wikipedia

Forbidden Wife: The Life and Trials of Lady Augusta Murray, Julia Abel Smith, The History Press, 2020.