©Carole Tyrrell

As you pass by a cemetery do you ever think that you hear celestial music drifting on the air? Maybe it’s because there are so many musical symbols to be found within them – violins, trumpets, guitars and harps to name a few.

This month, I’m going to be discussing the harp. It may immediately bring visions of angels in pristine white gowns, perched on clouds, plucking away on golden harps to mind. Harps have that ethereal quality.

Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

I found many online images of statues of angels playing harps in cemeteries worldwide but all on stock photography sites. It’s a reassuring image of heaven as a place of peace and calm. According to Alison Vardy, a professional harpist, the word ‘Harp’ or ‘Harpa’ comes from Anglo-Saxon, Old German and Old Norse words for ‘pluck’ as in plucking the strings.

However, when I first considered writing about the harp as a symbol I did think about linking it with St Patrick’s Day. After all, it is the national symbol of Ireland and also appears on Guinness cans and bottles.

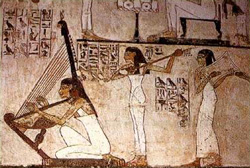

But this musical instrument has an ancient tradition and images of harps have been found in wall paintings in France dating from 15,000 BC. They also appear on Ancient Egyptian wall paintings from 3000 B.C.

In fact, it’s one of the oldest musical instruments in the world and was originally developed from the hunting bow. In this image the harp being played still resembles the hunting bow as it doesn’t yet have the pillar attached. This didn’t appear until the Middle Ages and was added to support additional strings. The earliest known image of a harp is a Pictish carving on an 8th century stone cross.

‘Harps played an important part in Irish aristocratic life. Harpists were required to able to evoke three different emotions in their audience. Laughter, tears and sleep.’ Alison Vardy (the last emotion being very appropriate for a cemetery)

The harp is associated with St Cecilia who is the patron saint of music. She was a Roman martyr who is reputed to have sung to God at her wedding and also as she lay dying after being beheaded. You can read more about her life here; https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Cecilia.

St Cecilia’s feast day is 22 November but her association with music didn’t begin until the 15th century. She was then depicted as playing at an organ or either holding an organ or organ pipes.

The harp also appears as an instrument of healing in the Old Testament. In Samuel verses 16-23, David plays the harp for Saul in order to drive out the evil spirit that afflicts him. Harps are also mentioned in Genesis and Chronicles.

When I first saw this monument in Brompton Cemetery I thought that it had to be dedicated to an Irishman. But it is in fact on the grave of a Welshman, Henry Brinley Richards (1817-1865), who was born in Carmarthen.

Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

He was originally destined for a medical career but music was his real calling. However, he didn’t play the harp as, instead, he played the piano. He was discovered after winning a prize for his arrangement of a traditional song, ‘The Ash Grove’, at the 1834 Eisteddford in Cardiff. This really opened doors for Henry as he was able to study at the Royal Academy of Music under the patronage of the Duke of Newcastle. Henry won two scholarships while studying at the Academy and after graduation he taught piano there. He travelled to Paris and met Chopin and he has over 250 compositions listed in the British Museum catalogues of printed music. But his most famous piece of music is ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales’ from 1862. Henry never lost his Welsh connections. Pencerdd Towy is his bardic name and not, as I originally thought, another Welsh town. Bardic names were pseudonyms and part of the 19th century medieval revival. I did research bardic names but I have to admit that I was none the wiser. And the meaning of the harp that sits so resplendently on top of the monument? It’s the national instrument of Wales which I didn’t know until I began researching this post.

©Carole Tyrrell

The other example is from the Rosary Cemetery in Norwich. This is a non-denominational cemetery and rises in tiers above the city. It’s an interesting group of symbols and is dedicated to a woman, Sarah Russell nee O’Brien (1869-1899) and there may be an Irish reference with the harp and her maiden name. She died young, aged 30, in Kansas City, USA. Sarah was born into a performing family as her father, Archibald O’Brien, and siblings were all equestrians. I found the family living in Leeds in the 1881 Census and they must have really stood out amongst their respectable, aspiring middle class neighbours. Equestrian was listed as their occupation. She married into another family connected with animals as her husband, William, was part owner of a zoo. One of her sisters, Irma O’Brien, wrote the epitaph:

‘To my dear sister Sarah Russell,

‘Soeur bien aimee reposee en paix’

which translates as:

‘Beloved sister rest in peace.’

On this monument note that the harp has no strings and so cannot be played. This indicates that the music of life has ended. There are also other variants in which a string on the harp is broken which again means that it can no longer be played. The music has been stilled by death. The cloth, nicely detailed to simulate lace with the holes, indicates the curtain between the world of the living and the dead. However, the broken column is said to denote a life cut short. I have always understood this to mean that the backbone of the family, the support of the family, had died and this is usually on a man’s grave. But maybe Sarah was the support of the family after all. For me, it’s the unstrung harp that is the most poignant symbol of the group.

So the harp can have several associations; a musical instrument, a symbol of national pride, a representation of life and death and also with angels. However, according to J C Cooper, it can also be viewed as the ladder leading to the next world with the harpist being Death – an interesting allusion. There is also a link with the Celtic God of Fire, Dagda, who calls up the seasons and whose playing originally brought about the change of the seasons and made them appear in the correct order. This is the harp as an instrument of power particularly with Dagda. This is very different from pensive angels in a heavenly harp choir. However, it’s good to understand the contrasts in how it is used and how it’s perceived in other cultures.

I hope that you all stay well and safe in these unprecedented times.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading:

An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, J C Cooper, Thames & Hudson, 1979

https://churchmonumentssociety.org/resources/symbolism-on-monuments

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2109764

https://tuisnider.com/2015/10/12/historic-cemetery-symbols-what-does-a-harp-mean/

https://artofmourning.com/2010/11/21/symbolism-sunday-the-harp/

https://www.undercliffecemetery.co.uk/gallery/funerary-art/

http://www.thecemeteryclub.com/symbols.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Cecilia

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Cecilia

https://bardmythologies.com/the-dagdas-harp/