View of Lamb House pets cemetery © Carole Tyrrell

In April, I was on a literary weekend in Sussex and Kent. We made the town of Rye our base. The town has a rich literary tradition with several famous writers having lived there. Several of them were lucky enough to live at Lamb House, a red brick Georgian house with spacious rooms and a garden that was just beginning to take shape on my visit. Neatly labelled rows of vegetable seedlings gave an indication of what was to come later in the year. There is a magnificent view of St Mary’s church from an upper window and Henry James is commemorated with his writing desk and ‘The Telephone Room’. I love finding pet cemeteries as I find them fascinating and touching.

© Carole Tyrrell

Lamb House is now owned by the National Trust and when I last visited over 20 years ago, it looked very different. There was an upstairs tenant – lucky them! Now the upstairs rooms have been opened to visitors and on my visit there was an exhibition, ‘Ghost Written’, which featured the house’s most well known writers through their ghost stories.

Lamb House Rye Shared under Wiki Commons © Jerrye & Roy Klotz, MD

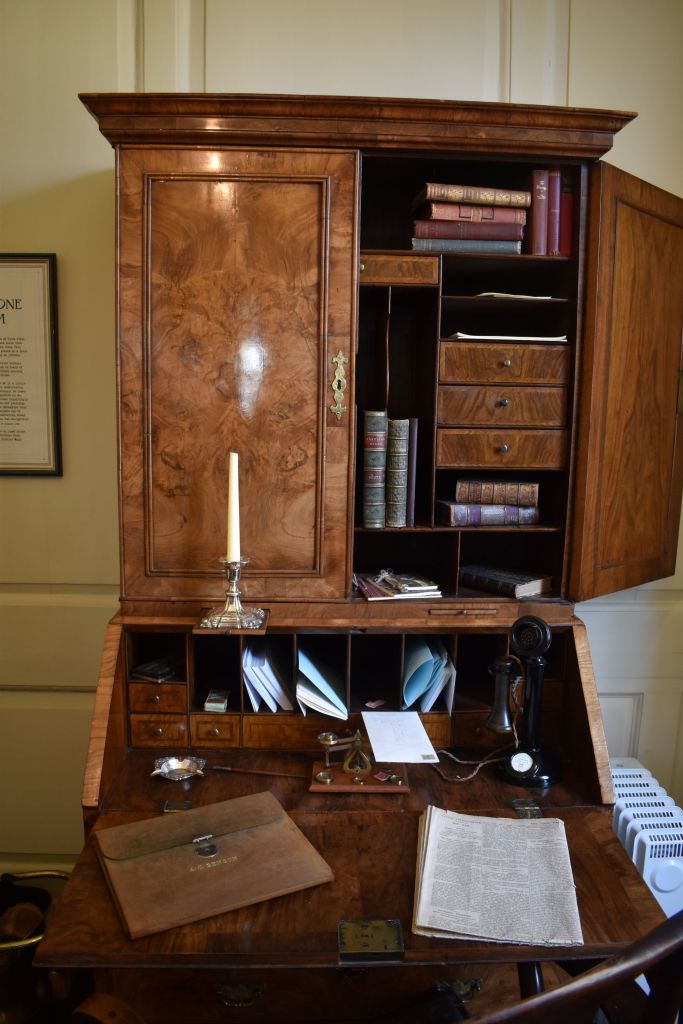

The American writer, Henry James, (1843-1916) wrote three of his most famous books at Lamb House: ‘The Wings of the Dove’, ‘The Ambassadors’ and ‘The Golden Bowl’. He discovered Lamb House while visiting a friend and instantly fell in love with it. He leased it in 1897 and, two years later, he finally bought it.

The house appears in his novel, ‘The Awkward Age’, where it is Mr Longdon’s home. During James’s time there a literary circle came into being that included Rudyard Kipling and H G Wells amongst others. In 1916, James was very ill in London and wanted to be taken back to Lamb House but he was too ill to be moved.

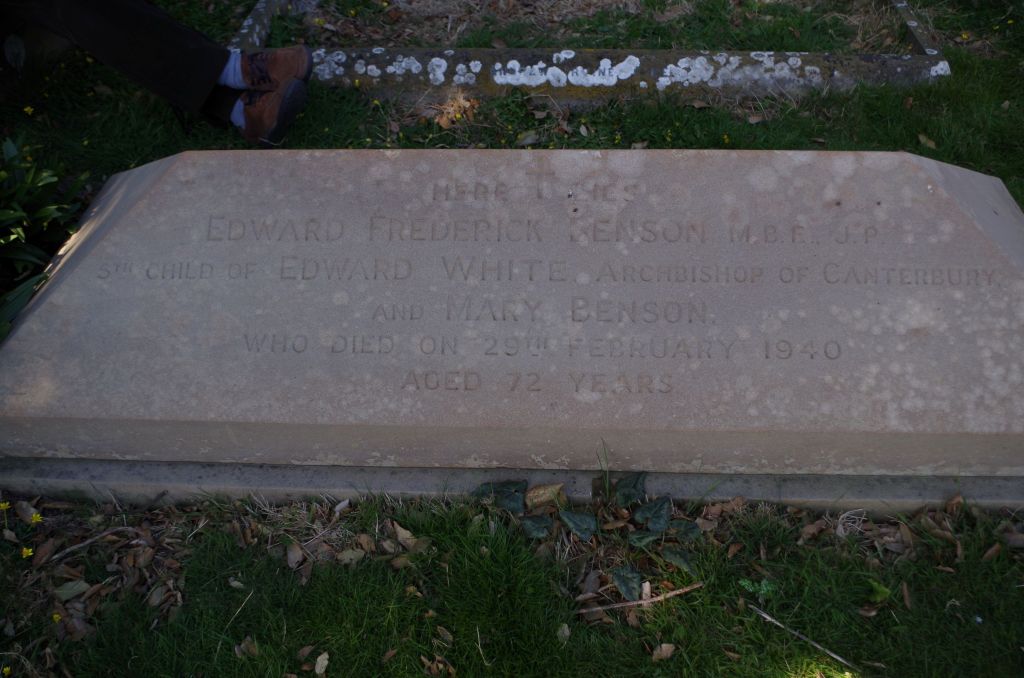

He was followed by E F Benson (Edward Frederic) Benson (1867-1940) who is known for his Mapp and Lucia novels which are set in a fictional town called Tilling that was based on Rye. They were adapted and made into a successful TV series. I know him through his ghost stories or ‘spook stories’ as he called them. He became Mayor of Rye twice and was awarded the Freedom of Rye which was the town’s highest award. He is buried in the local cemetery on the outskirts of town. ‘Fred’ as he was known bequeathed two colourful windows, the East and the West, in the local church, St Mary’s.

View of Fred Benson’s monument © Carole Tyrrell

Another view of Fred Benson’s monument.© Carole Tyrrell

Other writers who lived at Lamb House were Montgomery Hyde and the prolific author of ‘Black Narcissus’, Rumer Godden.

It was in the south western corner of the garden that I found the pet cemetery which was dedicated to Henry James and Fred Benson’s pet dogs. I remembered it from my first visit where it was hidden behind vegetation. The cemetery is a small collection of headstones. There are no cats as, although Henry James, was;

‘A great lover of animals he would chase them (cats) away from the garden’

National Trust guidebook

The first headstone in what James called his:

‘domestic mortuary’

was dedicated to Tosca, his black and tan terrier who died in 1899.

Tosca was followed by Tim who was another terrier, then came:

‘my admirable little Peter’

Then there was another terrier, Nick. But James’s heart was undoubtedly given to Maximilian or Max, a red dachshund. According to his owner Max had

‘a pedigree as long as Remington Ribbon.’

He also described Max as:

‘the gentlest and most reasonable and well mannered as well as most beautiful small animal of his kind to be easily come across.’

Max loved being taken on long walks but, due to his love of chasing sheep, had to be kept on a long leash.

Henry was very upset at having to leave Max behind when he went on an extended trip to the US. He wrote to his lodgers of his homesickness and how much harder it was when thinking of:

‘poor sweet pawing little Max.’

© Carole Tyrrell

© Carole Tyrrell

© Carole Tyrrell

Fred Benson also adored dogs and his favourite was a collie called Taffy. This is a photo of them together and Taffy is also commemorated in the East Window of St Mary’s church.

From the exhibition, ‘Ghostwritten’ at Lamb House

Taffy is the black dog in the lower part of the window, East window, St Mary’s, Rye. © Carole Tyrrell

© Carole Tyrrell

Rumer Godden loved Pekingese dogs and she owned several throughout her life.

I didn’t recall the pet cemetery being so large but the Trust’s intention is to recreate the garden so that it resembles

‘ the space that delighted and inspired Henry James and Fred Benson’

National Trust guidebook

I found the little cemetery with its little plain, simple stones very touching and a poignant reminder that these much loved pets were not forgotten. And as I read the names on the stones they seemed to come alive again racing around the garden at play.

©Text and photos Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated.

References and further reading

National Trust guidebook