St Eanswith, Brenzett © Carole Tyrrell

The churches of the Romney Marshes are isolated and you’ll need your own transport to visit them. But there are hamlets and villages here and there and I could imagine how it must feel in mid-winter with dark short nights.

However it has long been one of my ambitions to explore the churches that are on the marshes. So when I was offered the chance I didn’t hesitate. It was a wonderful Spring day, sunny and bright, and we were all eager to explore the Marshes.

Our first church was St Eanswith in Brenzett. This was a plain little church with a candlesnuffer steeple on top of a small slope and was surrounded by a small churchyard dotted with daffodils. There was an azure blue sky and a hare was spotted racing across a bare field at the back of the church. It’s one of the smallest churches on the Marshes and is dedicated to a 7th Saxon princess who founded a nunnery in Folkestone in 630AD. There is now nothing left of the Saxon building and the present church can only be dated back to the 12th century when the Normans rebuilt it.

A small statue of St Eanswith over the top of the porch. © Carole Tyrrell

A large Maine Coon cat, who was obviously returning from a night out through the churchyard to its home in the little straggle of houses nearby, caught sight of us and tried to hide by running from patch after patch of daffodils. Then its owner came out of the house that it ran into with another Maine Coon cat!

Hide and seek © Carole Tyrrell

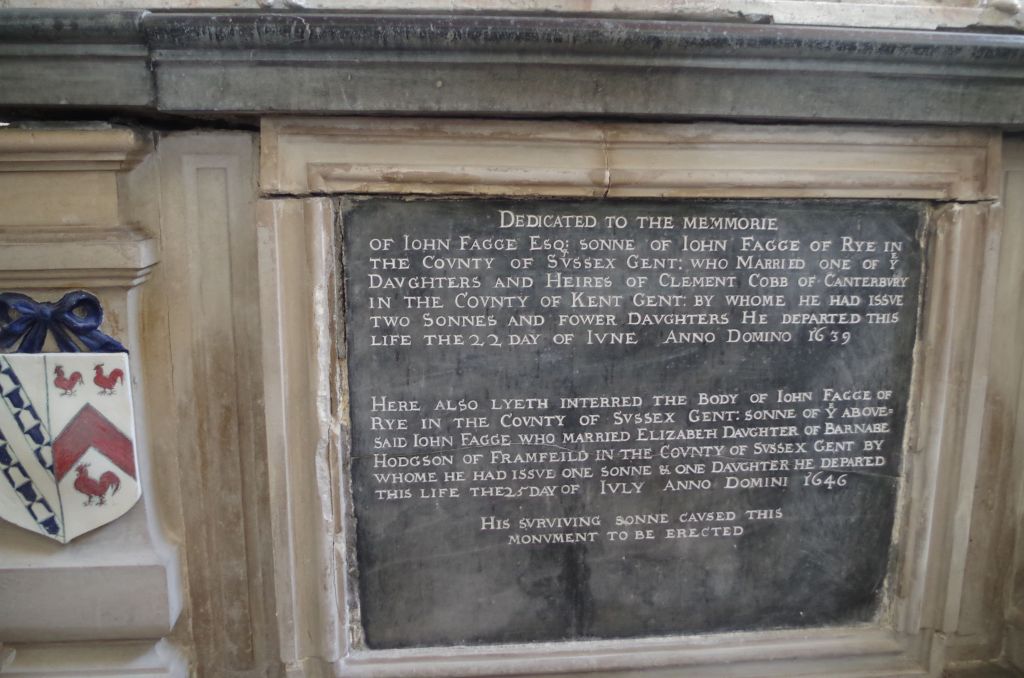

Inside St Eanswith it was plain, with white washed walls and dark wood pews. The pulpit had a raised roof panel which I’d not seen before and at the altar end of the church was the table tomb that we had come to see. This was the Fagge monument and is the only monument in the church. It is dedicated to a father and son, both confusingly called John, and it is a pair of alabaster sculptures of two men in fashionable 17th century clothes. The man in the foreground is portrayed as lying on his back on a sculpted cushion with his left hand on his chest while the man behind is lying on his elbow with his right hand under his chin and his left hand on his left leg. There are visible cracks and damage with repairs which you would expect over the centuries. They are beautifully sculpted. There are small coats of arms beneath the figures at corners which bring a small splash of colour. John Fagge the elder died in 1639 and his son and heir died in 1646.

The Fagge monument, St Eanswith. © Carole Tyrrell

Close up of the Fagge monument. © Carole Tyrrell

Close up of hands showing the ravages of time. © Carole Tyrrell

Epitaph to the Fagges and one of their coat of arms.© Carole Tyrrell

This is the monument that inspired one of E Nesbit’s most famous stories, ‘Man Size in Marble’ which was adapted by Mark Gatiss for the 2024 BBC Christmas ghost story and retitled ‘the Stone Woman’. A young married couple have moved to the country and their housekeeper tells them of a certain night when something walks from a local church to their house. They take no notice of this but when the husband is called away and leaves his wife alone in the house….you can read the story here: The Project Gutenberg ebook of Grim Tales, by E. Nesbit.

This is English folk horror clashing with modern reasoning and belief. Nesbit creates the dark countryside so well and also the central characters incredulity at what they are being told. They are still in love with endearments such as ‘wifie’ and ‘dearest’ which makes the ominous events that are about to happen all the more shocking.

E Nesbit c. 1890 Shared under Wiki Commons

E Nesbit (1858-1924) is most known for ‘The Railway Children’ which was first published in 1905 and has never been out of print. It was also a classic and well loved childrens film. Some of her other children’s stories have also been adapted for TV. But she also wrote ghost stories, some of which were recently published by Handheld Press in the collection ‘The House of Silence.’

She was only 4 when her father, an agricultural chemist, died. Edith’s sister, Mary, suffered from ill health and as a result the family travelled in the UK and France. She died in 1871 of tuberculosis after becoming engaged to the poet Phillip Bourke Marston. After Mary’s death, Edith and her mother lived in Halstead Hall, Halstead in Kent which is considered to be a possible location for ‘The Railway Children’. When she was 17 they moved to Elswick Road in Lewisham.

She married Hubert Bland on 22 April 1880. They met when she was aged 18 and at 21 and 7 months pregnant they tied the knot. It was a difficult marriage to say the least as he was always being unfaithful. Edith had 3 children by him and adopted 2 more from one of his long term affairs. It was a complicated family. She and Hubert were both fervent socialists and joined the Fabian Society, jointly editing its journal ‘Today.’ But this work often took second place to Edith’s writing as she became more successful. The Fabian Society ultimately became part of the Labour party.

From 1899-1920 she lived at Well Hall Eltham. The house is long gone but the garden remains as a public park. She also had a second home at Crowlink, Friston, East Sussex when she entertained.

Bland died in 1918 and she married her second husband, Thomas ‘the Skipper’ Tucker in Woolwich where he was the captain of the Ferry. They both lived at St Mary’s Bay, Dymchurch at their house ‘The Jolly Boat’ where she died on 4 May 1924. It may have been from lung cancer as she was a great smoker. Tommy died at the same address on 17 May 1935. To read more about Edith and her life please visit: https://edithnesbit.co.uk

It was such a privilege to see the Fagge monument in the flesh so to speak and also a writer’s inspiration. I could easily imagine Brenzett on a winter’s night, the little terrace of houses with their curtains drawn and lights out as something stirs and moves within the small church and suddenly the top of the tomb is empty and something that shouldn’t be is walking…..

A Spring Saunter in the footsteps of E Nesbit Part 2 her late life on the Marshes

© Carole Tyrrell photos and text unless otherwise stated

Brenzett, Church of St Eanswith — Romney Marsh Historic Churches Trust

St Eanswith’s Church, Brenzett, Kent

The Project Gutenberg ebook of Grim Tales, by E. Nesbit.

https://edithnesbit.co.uk The Edith Nesbit Society