The King of Terrors headstone, St Larence in Thanet, Ramsgate. © Carole Tyrrell

It was in the churchyard of St Laurence in Thanet, Ramsgate that I found this gleeful skull wearing a crown. The churchyard has a plethora of winged souls or children’s heads with wings but there is also a scattering of fine skulls as well. This particular skull has bat wings on either side of its head but more on these later. I consider it to be a personification of The King of Terrors which is another name for Death.

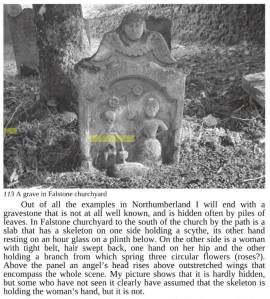

The left hand side of the headstone showing the word ‘Mary’. © Carole Tyrrell

The words on the righthand side of the headstone are unreadable. © Carole Tyrrell

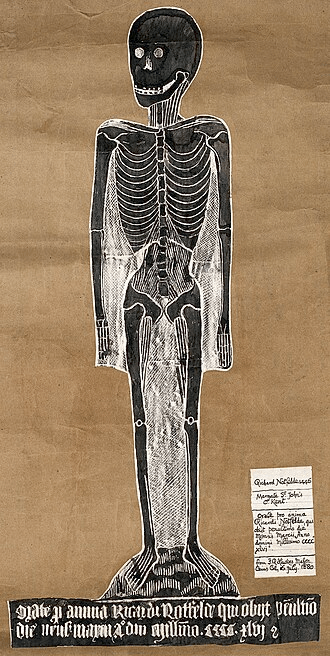

The headstone is very weathered and most of the epitaph has now gone. According to the 1895 book published by Charles Cotton on ‘St Lawrence (Laurence), Thanet (Ramsgate)’, it could be either the last resting place of:

‘Mary, wife of Cornelius Martin, died 15th December 1728 aged 57 years’

Or

‘Mary, wife of George Martin, died 10th January 1727 aged 38 years.’

On closer inspection, the name Mary can still be seen but what remains on the right-hand side of the headstone is illegible although I did spot an ‘i’. This is what led to my supposition that it might be one of these ladies who is buried there.

On first glance it doesn’t look like a very comforting symbol with its stark representation of death. There is a very sobering verse written by the Rev. George Crabb (1754-1832) in which he mentions the King of Terrors:

‘Death levels man – the wicked and the just,

The wise, the weak, the blended in the dust,

And by the honours dealt to every name,

The King of Terrors seems to level fame.’

This reminds the reader that Death makes all men and women equal despite their rank when alive.

The King of Terrors is usually depicted as a skeleton brandishing a scythe, an arrow, a spear or a dart. This magnificent example comes from Cralling Old Parish churchyard in the Scottish Borders. It’s a gleeful skeleton holding a scythe which is the symbol most associated with death.

The King of Terrors, Crailing Old Parish Churchyard. © Walter Baxter shared under Creative Commons Licence Geograph NT6820

Also in Scotland, Greyfriars Cemetery in Edinburgh abounds with macabre symbolism on its monuments and is well worth a visit if you’re ever visiting the city. I have seen it for myself and it is an amazing place. The lively skeleton depicted on the headstone of Surgeon James Borthwick is known as ‘the dancing skeleton’ and is very impressive. Please follow the link below and scroll down to see it.

Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh: The Ultimate Guide | My Macabre Roadtrip

The monument is large and measures 4m x 2m so you won’t miss it and is the largest one in Greyfriars. The skeleton is not only holding the Book of Destiny but also a large scythe. It is ultimately a ‘memento mori’ which is Latin for ‘Remember you must die.’

There is also one in the celebrated Rosslyn Chapel, near Edinburgh (don’t be put off by the Dan Brown associations) as it is such a fascinating place to visit.’

Click on this liGenealogy Tours of Scotland: A Month of Scottish Gravestones – The Dance of Death

All of these images emphasis the role of The King of Terrors as the King of Death or the Grim Reaper. For what else could Death be but a terror as it’s the unknown.

However, in this detail from Alice Stone’s headstone in the churchyard of All Saints, Staplehurst, Kent, a winged figure, presumably the Devil, is triumphantly holding a dart, is standing over a fallen skeleton whose crown has fallen from his head. Has the Devil beaten Death? Is the incumbent doomed to a life in hell?

The King of Terrors is also a psychopomp. This comes from the Greek word, ‘psychopompos’ which means ‘the guide of souls.’ They appear in many religions and forms such as spirits, angels, demons and gods to guide the deceased to the afterlife.

Anubis and the King – tomb of Horemheb 1323-1295 BC Metropolitian Museum of Art. Shared under Wiki Creative Commons

Charon and his boat on a funerary relief ca 320s BC shared under Wiki Creative Commons.

The most obvious examples are Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of the underworld, Charon the Greek ferryman, the Goddess Hecate and the Norse Valkyries amongst a host of others. The psychopomp is also a personification of death and often represented with a scythe and given the title of ‘The Grim Reaper’ – the reaper of souls. This is one of the earliest images of him and dates from 1460.

One of the oldest paintings with conventional ‘Grim Reaper’ elements, a skeletal character with a scythe (circa 1460 by Jean Fouquet) shared under Wiki Creative Commons.

The King of Terrors first appears in the Bible in the Book of Job 18:14:

‘His confidence shall be rooted out of his tabernacle, and it shall bring him to the king of terrors.’

This is part of a chapter emphasising destruction and death for those who do not keep to the righteous path. However, I am indebted to the vastpublicindifference blog for the next earliest use of the name in a printed pamphlet. He is mentioned in William Prynne’s ‘Perpetuite of a Regenerate Man’s Estate’ in 1626:

‘If once you have the smallest dram of time and saving grace, you need not feare the very King of Terrors, hell and death, you need feare the most that men or divells (devils) can do to you. They cannot seuer (sever) you from the love of God, which is Christ Iesus (Jesus) your lord, not yet disturbe you from the state of Grace.’

He also appears in nearly 200 books in English pre-1700.

However, the King of Terrors, the Grim Reaper or whatever you choose to call him is not a very comforting image for those left behind. So, it’s no wonder that, as the years went on, these very stark symbols began to be replaced by the ‘winged souls’. They gave a more hopeful image of another life after death. There’s also the batwings on either side of the skull to consider.

Bats were considered to be the spirits of the dead and associated with evil as the Devil traditionally had the same type of wings. Sometimes the skulls are given two different types of wings; on one side they are feathered and on the other is the batwings.

Bats can also be seen as guardians between physical and spiritual worlds. They were supposed to guide souls through transformation or metamorphosis: renewal, death and rebirth. So, the use of them is very appropriate on a funerary monument. In China, for example, they are seen as symbols of good luck, longevity and rebirth.

So, within this one symbol there are two meanings. One is that the person has encountered the Grim Reaper and has died whereas the other suggests that they are going to be reborn to everlasting life. It was an interesting symbol to see on my churchyard visit although the skull does look a little too enthusiastic!

Text and photos © Carole Tyrrell unless otherwise stated

References and further reading

The History and Antiquities of the Church and Parish of St Laurence (Lawrence), Thanet (Ramsgate) Charles Cotton, 1895 via Kent Archaeological Society

King of Terrors | Gravely Speaking

King of Terrors Gravestone © Walter Baxter cc-by-sa/2.0 :: Geograph Britain and Ireland

Vast Public Indifference: Death: “King of Terrors”

Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh: The Ultimate Guide | My Macabre Roadtrip

The King of Terrors takes a rest | Gravely Speaking

Job 18 KJV – Then answered Bildad the Shuhite, and – Bible Gateway

Genealogy Tours of Scotland: A Month of Scottish Gravestones – The Dance of Death